Emotional Eating and Metabolic Health

Emotional eating is the habit of consuming food as a response to negative emotions. Also widely known as comfort eating and stress eating, it is important to understand that stress is only one potential cause of emotional eating. It is generally used to describe eating in response to sadness, stress, frustration, nervousness, and even boredom. Emotional eating occurs in the absence of hunger. It refers to the ingestion of food to regulate one’s emotional states.

The difference between physical hunger and emotional hunger

Emotional hunger is very different from physical hunger. There are very distinct ways to tell if your eating is because of physical hunger or responding to an unmet emotional need.

Physical Hunger

Physical hunger comes gradually and builds over time. It is a complicated sensation that is indirectly linked to the need to eat. The sight, smell and imagination of food can stimulate hunger. When you are hungry, the feeling of your tummy rumbling is actually your stomach contracting in order to push any remaining food to the intestines and is called borborygmus. The stomach also releases the hunger hormone called ghrelin which triggers the feeling of hunger. Your vagus nerve, which is the longest of your cranial nerves, shares information from the brain surface to the tissues of your other organs. It connects the brainstem to the body. It also lets your brain keep track of the body and its functions, to that effect it sends signals about nutrients present in the body and how empty your stomach is. It’s also important to note that physical hunger carries no emotion with it. You are more likely to eat diverse foods and naturally know when to stop eating, thanks to the hormone leptin which signals suppression of appetite.

Emotional Hunger

This hunger comes abruptly and feels intense. It also makes you want certain kinds of food (high carb/junk/processed foods like chips, candy, packaged snacks, cereal). It involves voracious cravings and it strikes despite a full stomach. Importantly, emotional eating usually ends in feelings of guilt and shame.

Emotional eating involves psychological mechanisms. A leading psychology publication elaborates on the psychological determinants of emotional eating thus:

Restrained eating

Restrained eating translates into restriction and monitoring of what an individual eats. Food is constantly on the mind of restrained eaters, which may lead to them indulging in emotional eating in the face of negative emotions.

Impulsiveness

Acting without thinking can lead to individuals not assessing the consequences of their detrimental food consumption.

Reward sensitivity

It refers to the extent to which an individual is reactive towards the rewards of an action. In this case, some people are more receptive to the mood-enhancing properties of junk food or what is considered comfort food.

Stress eating & the sympathetic nervous system

Cortisol is a hormone considered to be the body’s warning system. It regulates blood pressure, increases blood sugar, and dictates sleep-waking cycles as well as how our bodies use proteins, fats, & carbohydrates. It is tethered to the fight or flight response. The stress response starts in the brain. In case of stress or perceived stress, the amygdala (area of the brain that contributes to emotional processing) decodes the sights and sounds and sends an SOS signal to the hypothalamus. The amygdala interprets the images and sounds. When it perceives danger, it instantly sends a distress signal to the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus communicates with the body through the autonomic nervous system. When you experience stress or sense danger (whether real or perceived), the sympathetic nervous system is mobilized. It stimulates the adrenal glands to set off the secretion of catecholamines (including adrenaline and noradrenaline). This leads to a spike in heart rate, blood pressure, and breathing rate. Blood is pushed to the vital organs. These are evolutionary adaptations to increase the chance of survival in life-threatening situations. Adrenaline gears the body for the fight or flight response. It causes a sharp, but short-lived, increase in insulin resistance. This ‘stress hormone’ can directly impact our glucose levels – by spiking the amount of circulating glucose. It floods the body with glucose to provide a prompt source of energy to fight or flee. At this point, stress can shut down appetite. Adrenaline amps up the physiological state and shuts down appetite.

As the initial deluge of epinephrine subsides, the hypothalamus rouses the HPA axis, consisting of the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland, and the adrenal glands. The HPA axis relies on a series of hormonal signals to moderate the sympathetic nervous system. If stress continues (as is the case during chronic stress) the hypothalamus triggers the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and incites the release of cortisol. Cortisol increases appetite and may also increase motivation in general, including the incitement to eat. Once a stressful episode is over, cortisol levels generally drop, but if the stress doesn’t go away — or if a person’s stress response persists — cortisol may stay elevated.

According to research, psychological stress may induce an upsurge in plasma ghrelin levels in humans. Ghrelin is a growth hormone and cortisol secretagogue that modulates appetite and weight regulation. The post-stress induced urge for uncontrolled eating is not acutely modulated by ghrelin elevation but related to the acute response of serum cortisol to stress.

According to a study, participants who reported one or more stressors during the previous day like arguments with spouses, disagreements with friends, or work-related pressures, burned 104 fewer calories than non-stressed women in the seven hours after consuming a high-fat meal. Researchers suggest that experiencing one or more stressful events the day before eating even a single high-fat meal can slow the body’s metabolism to a significant extent. Women could plausibly experience an 11-pound weight gain over the course of a year.

Emotional Hunger and Neurotransmitters

The science of emotional eating is what makes it particularly arduous to overcome. The reason emotional eating becomes a pattern is due to the way the body chemically responds to stress.

When we are stressed, our body releases a hormone called cortisol. <1.>Cortisol helps in regulating carbohydrates in our bodies which is why when we’re stressed or anxious, cortisol kicks in, making us feel like eating sugary, salty and high carb foods.

But that’s just the beginning. Eating these foods activates the pleasure centres in our brains via a rush of neurotransmitters called dopamine.

According to this journal, sweet foods activate the mesolimbic dopamine system. Dopamine, a chemical that gives us the feeling of pleasure, is released and reinforces the behaviour of eating sugary, high carb/fatty food. But this is very temporary, and eating high sugar food under stress carries a high risk of both obesity and type 2 diabetes.

New research shows evidence of dopamine being produced as a response to even merely anticipating eating certain foods. Imagine thinking about your favourite pastry with the knowledge that you will be eating it in a couple of hours. That anticipation may be enough to start the rush of reward-based dopamine.

Serotonin, the brain’s happy chemical—a shortage of which can lead to clinical depression—is also a part of the perceived rewards of emotional eating. Some foods, like chocolate, offer a spike in serotonin. Some foods also contain tryptophan, an amino acid necessary to make serotonin.

Research suggests that sugar lowers the stress response in the human brain. As a result, we may consume sugar as a prompt way to hold back feelings of stress. One group in a study was instructed to drink sugary beverages three times a day, while the other drank beverages with a substitute, aspartame.

The stress tests that the women took before and after the treatment indicated the generation of cortisol and activity in the hippocampus. The mechanism of this response is still under examination.

Stress Eating And Glucose Metabolism

Gluconeogenesis is the production of glucose by the decomposition of glycogen or from any non-glucose precursor. This process provides the body with glucose when it cannot be obtained from food, for instance during a fasting period. It involves the generation of glucose from lactate (derived from muscle and erythrocytes), glycogenic amino acids (mainly from the muscles), and glycerol (especially from fat) is carried out.

Under stressful conditions, the body derives glucose from cortisol by tapping into protein stores via gluconeogenesis in the liver. Steady spikes in cortisol over a period of time produce glucose, leading to increased blood sugar levels.

When we eat large amounts of unhealthy foods, our bodies produce excess insulin in an attempt to absorb it and regulate blood sugar in our bodies. Our bodies are more likely to binge eat (because of stress and the consequent surge of cortisol), and over time this makes our bodies more insulin resistant.

Anything that disrupts our regular homeostasis and consequently affects our metabolic pathways can be called stress. Anything that causes stress is called a stressor, and this can be both internal and external. The way we respond to this determines our overall health.

When we manage our stress in healthy ways, our bodies are more likely to want food because of physical hunger, which allows our body to produce normal amounts of insulin and utilize glucose as fuel. It then signals our brains to stop eating. Although new studies are needed to link these findings to humans, the study on mice revealed a vicious cycle where high insulin levels as a response to stress and high-calorie food promoted more eating.

Stress induces endocrine alterations, this includes the activation of hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal. Glucocorticoids and catecholamines are released in response to stress. These hormones also induce hypermetabolism which helps us cope with the energy demands of the body to fight stress.

Allostasis occurs when stress is chronic and our bodies adapt to constant stress resulting in a higher metabolism. Allostasis has effects on our glucose metabolism.

Hyperglycemia (high blood glucose) is the primary effect of stress because it allows more energy to cope with stress. As our bodies try to maintain glucose homeostasis, glucose pathways are affected. When our bodies are under normal circumstances, the glucose from what we eat and endogenous glucose (that’s generated by our liver) create the formation of glycogen in the liver. Stress inhibits gluconeogenesis in the liver and muscles.

When we are starving glycogenolysis occurs, where glucose is released from glycogen. When stressed, glycogenolysis occurs to fight stress. Many studies show low glycogen content in response to chronic stress.

When more insulin is released in the bloodstream it can cause inflammation in our arteries and also lead them to thicken and stiffen. This consequently puts stress on the heart.

Stress Eating & the HPA Axis

The interaction of the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and the adrenal glands is called the HPA axis. Our hypothalamus and pituitary glands are above our brain stem and our adrenal glands are on top of our kidneys. This is a very important system that regulates the body’s stress response.

The HPA axis is not only the ‘conductor’ of an appropriate stress response but is also tightly intertwined with the endocrine regulation of appetite.

The HPA axis is also part of the neuro-endocrine axis that regulates stress response via the secretion of glucocorticoids (cortisol). The HPA axis regulates the cortisol levels in the bloodstream and contributes to other significant physiological functions like blood pressure regulation. This is how it transpires.

Stress stimulates the release of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) from the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus which in turn stimulates the synthesis of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) from the anterior pituitary. ACTH subsequently triggers the production of glucocorticoids (GCs) such as cortisol or corticosterone in the adrenal cortex. The reversal of the HPA axis is being studied as a potential underlying cause of emotional eating. Cortisol is thought to induce habit-forming patterns which can result in an unhealthy eating model as a response to chronic stress.

Studies have shown that the deregulation of our HPA axis along with stress (and the consequent stress eating) is linked to obesity. There are holistic health factors that can affect our HPA axis, including the food we eat, environmental stressors, and emotional well-being.

Studies show that stress eating the foods we like or associate with stress eating can activate endogenous opioid release, which is the organic production of peptides that are released alongside other neurotransmitters from our HPA axis. Endogenous opioids are responsible for addictive behaviour, pain management, emotion and reward responses. Repeatedly rewarding the brain with emotional eating creates stress on our HPA axis, which leads to constant overeating. This dysregulation of our HPA axis is linked to increased intake of food and subsequent visceral fat in our bodies.

Stress eating and weight gain

Because of the reward pathways set up by the body in response to stress eating, we are more likely to keep eating and therefore keep gaining weight.

A study implicates the hypothalamus as a critical role player in the amounts of food we eat, and specifically the amygdala, in the emotional processing of hunger. I revealed that molecular pathways that are controlled by insulin lead to excessive weight gain. Dr Kenny Chi Kin Ip, lead author of the study told a leading publication that when stressed over a long duration of time and in the presence of high-calorie food, the mice in the study became obese more quickly than those that ate the same high-fat food in a stress-free environment says. The molecule at the heart of this brain pathway is called NPY. The brain generates this molecule naturally during stressful times, and the study showed that NPY triggers the intake of high-calorie foods in mice.

Studies suggest that stress may promote irregular eating patterns and strengthen networks towards hedonic overeating; these effects may be exacerbated in overweight and obese individuals. The factors underlying these and other behaviours that may contribute to obesity are slowly becoming understood. Research elucidates potential explanations for the stress-eating paradox, i.e. that stress can lead to both hyperphagia and hypophagia. Hyperphagia is an increased level of appetite that is associated with obesity. This usually occurs when there is injury to the hypothalamus. Hypophagia is the suppression of appetite where caloric intake is severely reduced and can happen because of external factors like stress or drugs.

Emotional Eating: Depression, Anxiety & Metabolism

According to WHO, 5% of adults suffer from depression worldwide. It statistically affects women more than men. Worldwide, at least 650 million adults are obese. Obesity and depression are linked and are a major health crisis.

A study shows a possible correlation between sweet cravings and negative emotions, such as anxiety and unhealthy eating behaviours.

People with depression may overeat to feel temporarily well, with a mood boost thanks to dopamine. However, over time, this creates a problematic cycle and puts our physical health at risk of diabetes, obesity, and metabolic disorders which are all finely interconnected.

Leptin, a protein that is produced from fat cells and regulates fat storage and appetite, and Ghrelin, the appetite stimulator that increases food intake and promotes fat storage, have been recognized to have a major influence on energy balance. Leptin and ghrelin also play a role in our mood. This has the potential to show us how chronic stress eating and mental illness like depression and metabolic disorders have a stronger connection than we think, in particular, to see if decreasing leptin (which is stress-induced) and an increase of ghrelin may result in obesity, diabetes, metabolic syndrome and heart disease. More studies are required in this area.

Food is tightly linked with direct neurotransmitter responses, which is why some foods like chocolate or caffeine allow us to feel different forms of pleasure or alertness. Being aware of foods and their effect on our brain is a necessary step in being more in touch with your unique responses to food consumption. (2.)

Research suggests that depression and emotional eating are positively associated and they both foretell higher 7-year increases in BMI and waist circumference. The effects of depression on change in BMI and WC were mediated by emotional eating. Night sleep duration moderated the connections with emotional eating, while age moderated the associations of depression.

How we can manage emotional eating

Our mental health, outside stressors, personal circumstances, and body health are all important factors when it comes to stress eating. There are many powerful steps we can take to make healthier choices and allow our bodies and minds to regulate themselves in positive ways.

Eat regular meals

Prioritise food timings and try to eat foods that are diverse, contain high fibre, protein and a balanced amount of carbohydrates. These foods are absorbed better by our body, keep our blood sugar in check, and allow us to feel satiated.

Know your emotional triggers

Make a note of the circumstances that usually trigger stress and emotional eating. Being aware of these triggers can allow you to be prepared for them and mitigate their effects. Understand that it might feel very uncomfortable to not cave in and eat when you feel triggered. A good practice to start would be to maintain a stress journal that can help you understand what triggers and eating patterns coincide with your high blood glucose levels. This also allows you to understand your body in response to the unique circumstances of your life. When you are more in touch with how your body thrives and achieve homeostasis via your eating habits you will develop intuitive eating habits.

Meditation and Mindful eating

Mindfulness meditation has been proven to offer many beneficial results for the body and mind. It might also help you to eat mindfully, which means having a stronger connection with yourself as you eat in the present moment. This allows you to feel body signals better, enjoy your food more, and stop eating when you feel full.

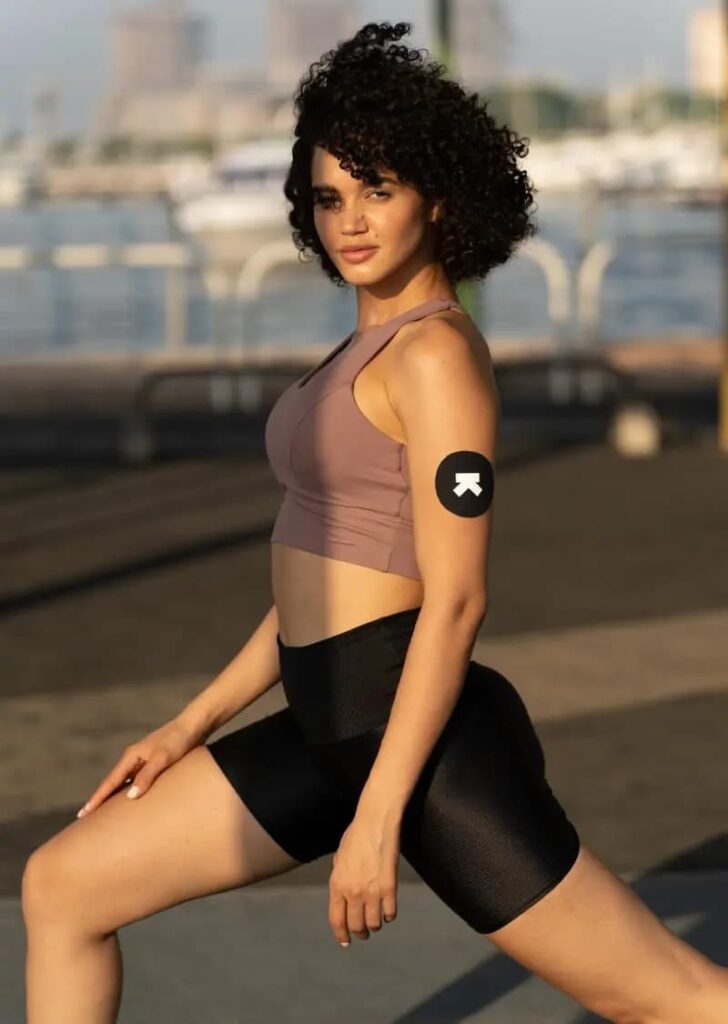

Exercise

Moving your body provides a whole host of benefits to the body and the mind. In particular, yoga seems to be most helpful when it comes to eating more mindfully.

A study suggests that emotional eaters who are physically active may still feel the impulse to eat when under emotional distress; however, they tend to choose more healthy foods to cope with this distress. Increasing physical activity could be an effective intervention strategy in preventing weight gain in emotional eaters.

Find the support you need

For many, just doing the above is not enough. Some people will struggle with mental health issues, disabilities, and circumstances that make healthy choices much harder to execute. It’s important for people who struggle with emotional eating, binge eating, and other eating disorders to seek therapy/professional help.

Intuitive Eating

Intuitive eating refers to a heightened awareness of physical hunger and a steady approach to healthy eating. It translates into steering clear of so-called yo-yo dieting patterns. Intuitive eating has been associated with reduced BMI, declined risk of cardiovascular disease, the higher consciousness of physical hunger cues and elevated pleasure associated with food. It allows you to be more present and observe the way you eat, how your body reacts to physical hunger and how it reacts to stress and emotional eating. It allows more agency in the way you choose to eat in comparison to a particular diet or rules. Breathing techniques, and keeping a regular meal schedule to help regulate and sustain healthy eating habits.

Conclusion

Emotional eating is a stress-induced response and very different from physical hunger. Emotional eating affects our brain significantly because of the flood of pleasure-reward neurotransmitters like dopamine. It results in eating high carb, fatty, and sugary foods, as a result of the stress hormone, cortisol, kicking in.

Emotional eating also interferes with our glucose metabolism, which has the potential to cause insulin resistance over time. Insulin resistance is linked to diabetes and weight gain. Our HPA axis is also deregulated by stress eating, which is linked to an accumulation of visceral fat in our bodies. Mental health, and in particular depression and anxiety, is associated with emotional eating and often creates a self-defeating cycle because of the direct effect food has on neurotransmitters that affect mood and wellbeing.

Exercise, a healthy and well-balanced diet, good quality and duration of sleep, can all play a part in managing your stress and regulating your emotions. Keeping a journal or eating mindfully (intuitive eating) is a healthy way to manage your unique responses to food.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are for general information and educational purposes only. It neither provides any medical advice nor intends to substitute professional medical opinion on the treatment, diagnosis, prevention or alleviation of any disease, disorder or disability. Always consult with your doctor or qualified healthcare professional about your health condition and/or concerns and before undertaking a new health care regimen including making any dietary or lifestyle changes.

References

- https://www.healthline.com/health/emotional-eating

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1471015314000191

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00925/full

- https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/325056#Understanding-what-controls-stress-eating

- https://www.verywellmind.com/eating-in-response-to-emotion-4001635