Introduction Of Podcast

As we grow older, it is imperative for us to change our longevity protocols. To discuss this at length, we’re joined by Dr. Howard Luks, a sports scientist and orthopaedic surgeon. Dr. Luks has a wealth of experience in the field of sports injuries and he shares the various strategies one can implement as they enter their 40s, 50s & 60s. Dr. Luks talks on what all things should one look out for and how things change for us as we age. You would not want to miss this. Tune in.

Timestamp

- (00:00 – 01:27) – Introduction

- (02:16 – 04:07) – Dr. Luks’ Journey Into Medicine

- (04:31 – 11:37) – Athletes & Thier Metabolic Health and The Power Of Biomarker Data

- (12:18 – 20:00) – Dr. Howard’s Views on Data vs Instinct

- (20:47 – 24:33) – Which Lifestyle Tweak Is The Most Efficient?

- (24:43 – 35:23) – Longevity On Different Life Stages

- (35:32 – 39:51) – Top 3 Longevity Advice From Dr. Luks

Key Takeaways – Transcripts

Intro (Mohit): Historically speaking, longevity in humans has increased dramatically around the globe. According to the United Nations, the average person born in 1960 could expect to live to 52.5 years of age. Today, that average is 72. But are we really living meaningfully despite the increase in life expectancy? Are we making the most of this lifetime? We will unpack this in today’s episode. We’re joined by Dr. Howard Luks, a widely respected orthopedic surgeon and sports medicine specialist who has spoken, written, and researched a lot on longevity. We understand from him what his formative years were and how he got into the field of sports medicine. We then start unpacking on longevity and the many facets of it. Along with some of the critical protocols built around longevity, we expand on the age old subject – health span vs lifespan, what one should consider. Dr. Luks shares his perspective on this matter and especially at a later age, as before you hit your 60s, longevity protocols are different. This segment is the highlight, and you wouldn’t want to skip it. We wrap up the episode by discussing how we can efficiently combat aging with Dr. Luks sharing his top three essential tips on longevity. Let’s deep dive.

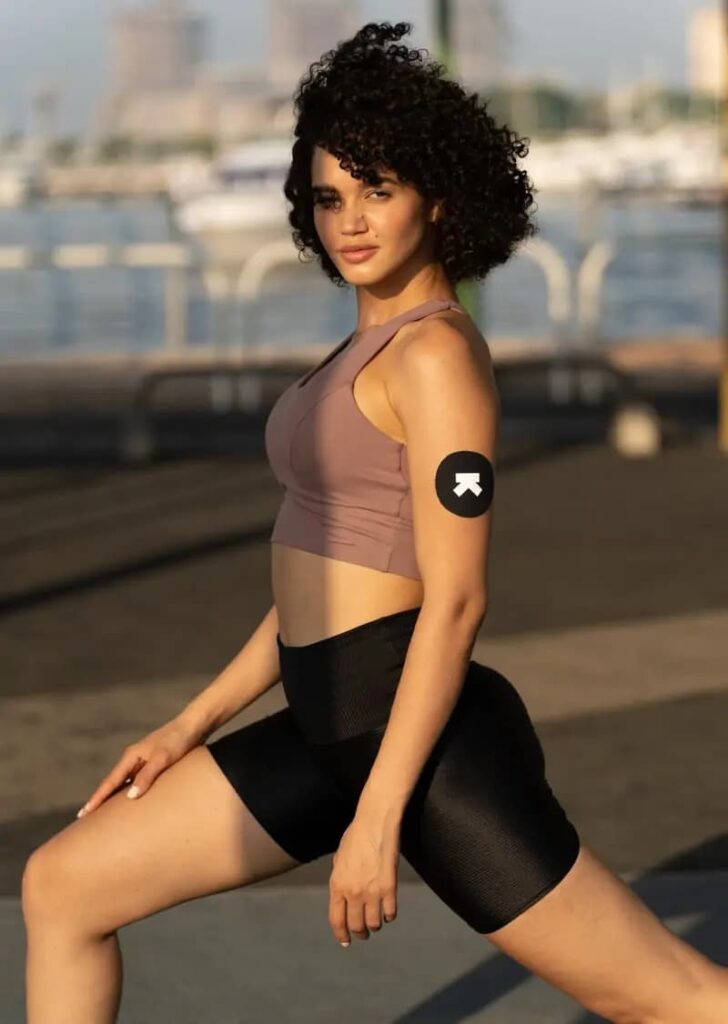

Question (Mohit): Hi, Dr. Howard. Such a pleasure to have you here. Really excited to welcome you on the Ultrahuman Podcast. I think one of the key cornerstones of when you say metabolic health and the goals of any sort of you can say domain of health is to actually now look at health in a more holistic way. And of course, when you say holistic health, you think about longevity. What’s really interesting is that you have recently written a book in the space of longevity, and of course, we would love to know more about it along the way. But before that, I would really love to understand from you, like, what was your journey that led you here? I think this space is such a wide and enormous space that there are learnings from, of course, athletes and athletic performance and the medical science side of things. But I would love to understand from your side, where did you actually start and what led you to actually think more about why longevity will be a need for people?

Answer (Howard): Yeah, sure. It’s a pleasure to be here. Thank you for the offer. For over 17 years now, I’ve had a very active orthopedic surgery website where I’ve talked about typical shoulder, knee, spine, and hip issues. And then because I’ve been a lifelong athlete myself, I just started to notice the changes that were occurring in my own response to training loads and running. And I started seeing friends with various diseases, and I sat up and took notice and I said, this can be a problem, so let’s figure out this longevity space. Let’s see what it has to offer. So I started writing, reading a lot, and I write to further my understanding. And so I started to put these posts on my website about heart disease, blood glucose, metabolic health, how metabolic health affects you from an orthopaedic perspective. They started to become very popular and at around the same time I started to notice my patients, which I was getting an older demographic in the office now were suffering. All the patients were starting to suffer from the same disease states type two diabetes, insulin resistance, non alcoholic fatty liver disease, hypertension, etc. And so I started to draw the associations between overall health and poor athletic performance, overall health, poor lifespan and health span. And I just started to dive deeper and deeper into this.

Question (Mohit): That’s really interesting because I think one of the things that you mentioned is that some of these learnings actually came from the athletes and you actually correlated athletic performance in some ways with metabolic health. What’s counterintuitive is the fact that when people think about health, I think people consider athletes to be at the top of their game. So what sort of insights or observations that you would have made around athletes and their metabolic health given the fact that athletes would normally be extremely active and with what their diet and their fuelling patterns as well?

Answer (Howard): Yeah, sure. Athletes in general, we have to push ourselves in order to achieve. And we have various energy systems in our body. The two main ones are fat oxidation and glycolysis. Lactate has a big role, but we can discuss that later. And when you’re young and these disease states are sort of very much under the radar, not revealing themselves in any meaningful way. You can get by and you can achieve and you can reach your goals. You can podium at a race, you can run a sub two hour half or sub three hour full marathon. But as you start to get older, these diseases such as insulin resistance, heart disease, et cetera, start to reveal themselves. As I say in my book and elsewhere, you can’t outrun a bad diet. And as you know, a lot of these diseases, taking insulin resistance, for example, are an area under the curve issue, meaning that the longer that you’re suffering from this, the longer that you’re exposed to the issues that cause insulin resistance, the more significant the consequences are going to be later. So some of the cardiology community are finding evidence of insulin resistance and young, thin college people who are not particularly active. But the presence of insulin is now being seen in 18 and 20 year olds, sometimes even younger. So the consequences of that 20 years later are going to be profound. So I started to notice in these athletes that when we discussed their training plans, what their goals were for the season, that they were having more trouble achieving them. And so I started to dive deeper into their overall health. We checked the number of biomarkers and did a number of tests and it wasn’t uncommon to find some evidence of insulin resistance, elevated LDL or inflammatory markers. And when we tried to correct some of those with changes in their training, we were often able to improve their performance.

Question (Mohit): That’s really cool. And one thing that I noticed when you mentioned insulin resistance in young people, I think one of the things that people actually don’t know, and I think would love to know more about from you is the fact that when people look at lupus insulin response. Just looking at Lupus might not really tell you the entire picture in this case, especially in young people, because their insulin levels might actually hide what the truth of the reality is. And probably a homer IR or a glucose tolerance may actually reveal a much better picture. I think a few months back, what we did was we were looking at some of the work of Dr. Craft around the insulin curves and the zones of insulin sensitivity and resistance. And I think what we also observed was that there is, of course, a lot of athletes who have good you can say in terms of good body fat percentage, and they’re sort of like at the peak in the early age, they might have much better insulin sensitivity by default. But then, even within those, at least there’s a grade of insulin resistance. And we were not able to map performance back then. But for sure, I think, given the fact that for the factors you mentioned, this is an area under the curve problem, so it compounds over time. So the cause definitely exists. The effect hasn’t happened yet. I think that could be one way to actually educate people in this space that you really look at your both glucose and insulin to understand more. Is that the right way to think about it?

(Howard): Yes, that is the right way to think about it. I did many glucose tolerance tests on people with measuring insulin levels at the various time markers. In addition to glucose levels, I also worked with a number of folks where they were wearing a CGM, and we would do a Pepsi or a Coke response. So if they could stomach it, they would, on an empty stomach, drink Coke or Pepsi, and we see what their response was. And we mapped it, record it, and then we go onto an aerobic base building program, zone two program, and we would see a change in their response over time. And that change was meaningful. But just the CGM response as a whole can be a challenge to interpret in the context of athletic performance, right? You have some athletes who will push hard and drop their glucose, and you have some that will push hard and they’ll raise their glucose, but there’s no signs of insulin resistance in them. And the prior one, the one with the low glucose response, is not a Keto or Paleo athlete. So it is a fascinating area that’s still wide open for study and interpretation.

(Mohit): Yeah, I love the fact that you mentioned that you tried out the Coke test or the Pepsi test as well, given the fact that I think this might actually be more acceptable by people to try out. And I think if you can map something that is mass available, probably because CGM values, in some ways you’re trying to I mean, fasting sugar intake with your CGM values, I think you’d be able to get a fairly decent sense of in some ways it’s like an oral glucose tolerance test as well, right?

(Howard): No, listen, when I wrote my book, I wrote it for the masses. I wrote it for everyone. So it upsets people at the high end of the curve who are exercising every day. Why did you talk about this? Why don’t you talk about this? Because I’m talking to the 95% who aren’t doing enough. And it’s the same in the glucose space. It’s very powerful for people who put a CGM on. Most people in the office who I put a CGM on, we lose £3 to £5 in two months. And it’s just because they started to see the response of some foods and they just made decisions based on what they thought might be a healthier choice. And when they see a decrease in glucose variability, they see a decrease in how high that spike is going to be when they take down a Coke or Pepsi. It’s very empowering for them.

Question (Mohit): Yeah, I think this is a phenomenal point that what you just mentioned is actually pretty much when we speak to folks, I think there’s a clear divide where a lot of folks say that this is not the right way to look at the science of insulin resistance or the science of insulin in general. And then, of course, other folks will start to believe in something like this. I think especially in the folks that you mentioned, people who are sort of like either have been dealing with chronic disease for a long, long time, those people a, b people who have been helping people get fit by different methods. C, I think a group of people who actually don’t want to look at data as much. I think there has been a slightly different type of response by saying that, hey, data drives anxiety and you shouldn’t really look at data and go by instinct. But I think my view of this is that, yes, the criticism is required to evolve the space, but some of that is also early markers of a new way to think about this space. And of course, people will have their opinion, but some of this criticism is, for the lack of a better word, not very well thought through. What are your views on the sort of criticism about this space?

Answer (Howard): Medicine is hard, and especially if you follow guidelines, right? I see someone who has an A, 6.2, a little bit of abdominal obesity, and they may or may not be a runner or cyclist, and their Apob is 150. So a lot of their markers are off. And they come to me and say, oh, my doctor says I’m not diabetic. I’m like, you’re going to be in less than five years versus what this ALMC means, and let’s work to change this so that you don’t become a type two diabetic by strict definitions and standards. And so whether they want to try CGM, great, we’ll do that, or we can just go and work on exercise program, changing their training. We’ve had great results with that. But it’s really hard to when you’re pushing these concepts to the masses, there’s going to be a lot of confrontation with the medical complex, and I think that’s what we’re seeing. I wear CGM a few times a year, and I find it very illuminating. I find it very empowering. I like to see low baseline numbers if I eat certain foods pre exercise or post. I like seeing the tremendous differences. I can eat a banana and not spike my glucose. Someone next to me can eat one and they’re going to 160. So, yeah, we’re going to hit resistance until uptake becomes more commonplace before the endocrine society starts to adapt this more meaningfully in this pre diabetic population. I really don’t like the idea of waiting on these people until they become a type two diabetic because you may not see them back again sometimes until their A1C is eight and nine, and then it’s very hard to correct us. And that’s where we start to see so many of the downstream consequences with and organ damage, kidney failure, blindness. Heck, even in my own space, you have an elevated A1C uric acid, cholesterol. You’re more likely to tear your tendons around your knee and shoulder and your Achilles. You’re more likely to have high inflammation associated with these metabolic processes. So if you have even mild arthritis, you may experience more inflammation than someone with my other arthritis who’s metabolically healthy. So you are going to experience more pain and more disability. So we’ve been able to get a lot of people with even my arthritis, but severe inflammation. We’ve been able to quiet down their knee pain by addressing their metabolic health.

(Mohit): Wow. I think there are two really interesting segues. The first one is really an observation. The fact that you mentioned that you can eat a banana and not spike your glucose. I mean, what it probably would have meant is the fact that the goal of the platform is to or the goal of cracking glucose and insulin is to actually develop significant insulin and glucose performance, or in some ways, glucose. Tolerance and not to basically not consume glucose, but then develop the ability to actually process glucose in a much better way than how people can today. And I think that’s a highly understated aspect of glucose monitoring as well, especially in non diabetic people, given the fact that one way to interpret the platform is to say that anything that spikes with glucose is actually bad for you, which is obviously not the right way. And there’s enough. I think the education where it needs to be created is the fact that you should be able to consume glucose and sugars and carbohydrates and like in a natural environment, because these are essential nutrients and macros. But you should do it in a way that your body is able to process these in a good way and over time your body should move in the direction of processing these in a much better way. Is that the right understanding of how, you are absolutely correct. In my book and elsewhere on my website, I don’t necessarily push any one lifestyle. With regards to diet, I happen to be a big fan of just whole food diet, mostly plants, but you can certainly have meat and complex grains, carbs, legumes, and I’m a big proponent of feeding your effort. So while some athletes can be purely fat adapted and ketogenic, it’s going to take them years to acclimatise to this and for their body to be able to perform. So I’m a big fan of taking in enough carbs to refill my glycogen sinks so I can go out and run as long as far as I want and my energies won’t be a rate limiting source. But you’re absolutely correct. I think it’s powerful to see the impact of ultra processed carbs and foods. Go cook up a pot of oatmeal for 20 minutes, throw in some fruit, eat that, and then go get a package of infant oatmeal and check out the difference in responses. They can be very illuminating where it’s the same theoretical food group, but one has been manipulated significantly and one hasn’t. So I think our downfall has been the ultra processing of the food. All the chemical engineers and scientists these food companies hire to figure out the perfect macro percentage in our foods that make us want to consume more. The use of high fructose corn syrup and fructose, which does not trigger our satiety. So we don’t feel full, we just keep eating. So, you know, the cards are stacked against us in many respects. So using the science and others to peer into our body for these spot checks to see what our responses are very powerful.

Question (Mohit): These are really interesting rabbit holes, I think on some day. And these are really controversial and interesting rabbit holes as well. Of course, there’s a lot said about the effects of fructose beyond just affecting your metabolic health directly, but sort of like messing up your entire energy systems and whatnot. And I think also processed seed oils and all those highly oxidizing oils as well. But I think to actually make it a little bit easier for people, let’s say somebody who is not diabetic discovers that they have low insulin sensitivity, maybe via glucose tolerance test. And let’s assume that this person is moderately active. Is there a specific protocol that exists for such people to actually look at their insulin sensitivity and to improve their insensitivity?

Answer (Howard): Not that I’m aware. They’re very well maybe. Remember, I am an orthopaedic surgeon, not an endocrinologist. I plan to space at a high level. I don’t drill down into rabbit holes and details. So, yeah, none that I’m aware of.

Question (Mohit): In a different way, what have you seen work the best for people like, is it putting on more muscle mass, reducing carb intake fixing your sleep? Let’s say if you were to pick one aspect of lifestyle that gives you the most bang for your buck, what would that be?

Answer (Howard): I usually push three and you name them and that’s increase your aerobic engine, your zone TV engine, your fat oxidation engine, sleep, you need 7 hours plus. And you have to push and pull heavy things. As your audience hopefully knows, our muscles are the largest glucose and glycogen sink. They need to be able to take the glucose from our bloodstream, process it and package it and form a glycogen so it’s freely storable and usable. But we need to build our aerobic or fat oxidation engine, which allows our body to preferentially use fat to drive our energy needs. And as we may or may not touch on further, one way we can assess that is lactate. Because if you have a very poorly developed aerobic capacity, you are going into glycolysis very early. And for some that’s walking. So there are times that I’ll bring my lactate meters into work and I’ll check some people and they have a resting blood lactate of o1.82. And when I get asked them to walk around the block once, their lactate will actually go up. So they are in glycolysis this whole time, which is not a very productive, efficient, healthy way of processing or partitioning energy in the body. The more that we can utilize our fat oxidation systems, the more access that we have to our energy, right? We have an infinite amount of energy available in fat stores. We have only a few hours worth in glucose or glycogen, but it’s a much more efficient fat oxidation is a much more efficient means of energy production in our body, much less demanding as well. So I push aerobic conditioning, probably the most accounts on dietary changes. I really ask them to sleep well and then we start a body weight program. Yes, I think that exercise is the most important, but we can’t negate or not consider the others.

(Mohit): So, longevity is hard work, right?

(Howard): Longevity is well, it can be simple, but as I say, those who exercise, run, workout, bike, etc. To we’re the 5% or 7% of people who do that. But there’s a dramatic percentage of people who view exercises work. It sounds like work. It’s painful, it’s sweaty, and they don’t enjoy it and they’re not going to do it. But they will walk and if you show them the response to their walking efforts, now they understand what’s happening inside them by their walking. And habits can be formed in 30 days. So is that hard? I don’t think that walking is hard and it’s not painful. I don’t think that getting 7 hours of sleep is hard unless you’re an insomniac I understand, and I don’t think that eliminating a few foods from your diet is incredibly challenging.

Question (Mohit): When you put it like that of course, I think there is definitely the 80 20 to health. The other segment that I wanted to make was around when you think about longevity, longevity before, let’s say your 60s & 70s is different drastically from longevity after your 60s & 70s. And then there is potentially a muscular skeletal aspect to that, which is there is increased fall risk and some of us obviously don’t see it before 70s & 80s. That fall risk could actually be like an important factor in determining longevity or health as you age. So what are some of those observations from the other side, basically from the musculoskeletal world in terms of when people think about longevity, how some of the ways in which people can prepare, if people think that longevity, or if not lifespan, then health span is the eventual goal for all people.

Answer (Howard): Sure, yeah. You cannot underestimate the importance of a well-functioning musculoskeletal system to ensure a proper health span and a meaningful lifespan. There’s a process known as sarcopenia, and it’s age program muscle loss. So from the age of 40 and on, you are losing a certain percentage of your muscle mass and corresponding muscle strength every year. And that’s going to accelerate after your mid sixties in some instances. Whether it accelerates more rapidly at a younger age because of metabolic syndrome, poor metabolic health, the answer is probably yes, but I can’t recall any papers that confirm that. So we all lose and suffer from poor balance as we get older. And you likely start to see these changes in 45 and 50 year olds where you’re catching your feet a little more often, you’re stumbling a little more with change in heights of the terrain you’re walking on or running on. I definitely saw the changes of myself when I hit my mid 50s, and we see people on the street hunched over using walkers and canes, and we just assume that’s a natural part of aging, or that it has to be, and that has to be our future. But it doesn’t. You can it’s far easier to combat the consequences of future sarcopenia than it is to combat sarcopenia once it’s arrived. So if you’re 40 years old out there saying, okay, I have to take a note and remember to start working out when I’m 60. No, you have to work out now because you don’t want that loss to kick in. Because we can’t actually reverse the loss, but we can slow down the loss and we can improve strength. It’s well proven that even a 90 year old with one resistance exercise session will build new muscle protein. But we’re not going to get back everything that we lost. So when we see our seniors who have these very thin legs and thin arms and hands and fingers, that’s loss of muscle mass. And so it has significant metabolic consequences because we’ve lost our largest glucose storage mechanism. But it has significant musculoskeletal consequences because with less muscle mass and strength comes less of an ability to stop ourselves from falling when we stumble. And so the fall risk will increase. If you didn’t break anything, you have less padding around your bones and joints because of the loss of muscle mass and it becomes harder to recover if you sustain the significant injury. So you take someone who is functioning at a lower capacity. They have an injury, they’re in bed or at rest for a week or two. Now they’re at 20-25% less capacity at the end of that recovery. So if they are not exercising and working out, that’s their new baseline because they’re not going to recover that capacity back unless they work out. So then they go on and fall again and this just becomes a spiral. It’s very well known in the orthopaedic space that there’s an epidemic of osteoporosis and it’s absolutely worse in poor metabolic health. And so if you fall and the risk is there for men, it’s one in five in men and one in three women and you sustain a hip fracture. 50% of people who sustain a hip fracture are dead in one year. That’s just the sad reality of the worst consequence. Poor strength, loss of balance, poor recovery mechanism.

(Mohit): And why does that happen? Is that because when people lose mobility the ability to have any sort of, you can say fitness routine or activity sort of like goes off balance or doesn’t exist?

(Howard): Why does what happen? Why do they die or why do yeah, they are functioning at their body’s maximum capacity just to remain upright and walk, right? They have no reserves. And if you get to the point where you’ve lost your muscle mass, your steps are short or your gait is wide base and you rely on a cane or a walker and now you injure yourself. Recovering from the surgical trauma is profound. The impacts on your body will take months to recover from and there’s not an emphasis on proper rehabilitation at afterwards. So these folks are less active, so they’re not moving as much. So they’ll get bed sores, they’ll get UTIs or urinary tract infections and that can cause sepsis, as, ken, pneumonia from not being active. So it just starts to manifest in many different ways.

(Mohit): This is a really understated aspect of aging, to be honest. I recollect that in one of the sessions and I spoke to a few folks who essentially will sort of like at a conference where we were talking to folks who were talking about how is the glucose technology relevant for people about, let’s say, 50 years of age? And I think some of the pointers that you mentioned were quite, you can say acceptable by people in terms of saying that, yes, I think diabetes is pretty common in people above 50s or 60s, because that’s how you age. This is how aging happens. You become diabetic. You become basically have less muscle mass and essentially have lower bone density or basically have higher risk of fracture. In some ways, it looks like we don’t consider aging as a disease, but more like eventuality, in some ways. And that seems like a problem.

(Howard): Look, I mean, we’re all going to age. It’s just a matter of aging well, right? Some of us have hit the genetic lottery and some haven’t. But we can combat a lot of the changes associated with aging so that we can improve our ability to make that terminal decade, the last decade, really meaningful. So that you’re not in a physician’s office. You’re not sitting down on your walker all day. You can participate in life. You can walk with your family. You can walk with your dog. That’s really important. I don’t want to live to 90 if I’m hooked up to devices and on 20 medications. Yeah, having to see a different doctor every week, that’s not my idea of an ideal terminal decade, which is the last decade that you’re going to live. You know, Peter Attia talks about this, and I agree with him, and I’ve said something similar for a long time. You have to think about the things that you are going to want to do when you’re 70, 80, 90 years old. And if you’re lucky enough to get to that age, what are you going to do now that’s going to allow for those activities to happen, right? You want to put a 40 pound suitcase in the airplane bin above your seat. Maybe you enjoy gardening. You want to carry a 50 pound bag of mulch to your backyard. Maybe you want to be able to lift your grandchild, who weighs 20-25 pounds. You have to think about this because if you don’t actively train that ability, you’re going to lose it. And if you don’t actively work your balance, prove your balance, you’re going to lose it faster than you would otherwise. So it helps to flip the coin on longevity and not say that I’m not going to age, but to say, okay, I understand, I’m going to age. We’re not going to get a pill out in the next 30 years. That’s going to prevent aging. And so what can we do now to make our last few decades easier to deal with fewer downstream consequences? How do we hold off sarcopenia? How do we improve our balance? How do we improve our ability to participate in life.

Question (Mohit): That’s really cool. So in some ways so many interesting aspects there. But I think the most interesting one that I think therapy to me was the fact that it’s sort of like in some ways, you can visualize it like an event that you’re prepping for and maybe like when you’re 70s or 80s and maybe there is a way to look at it from a functional training mindset perspective that here are ten things you need to do to actually prepare for, actually arrive at in case you arrive in your 70s and 80s and you want to do these ten things, these ten movements really well, these ten, you can say, capabilities that you need to have. And I think potentially in the next few years as this space becomes much more interesting for people, as people age, of course, naturally this is going to become a need and a problem for people as they will become aware. But I think given the fact that the space is really deep in terms of possibilities and diverse and deep in terms of possibilities, I would love for you to talk a little bit about your top three, like what do you consider as 80% of longevity? And I would love to in the podcast with that.

Answer (Howard): My top one is to build your aerobic engine, build your fat oxidation and for those who exercise and run, that means you’re going to slow down a lot more than you want to. It’s not okay for every run to be at 150-165 heart rate, even if you feel fine. Because yes, you’re improving, HIIT can improve heart health. But when you’re looking at overall health, building your aerobic capacity, which is operating below your first lactate threshold and improving your ability to oxidize fats is going to be one of the most important things that you’re going to do for your metabolic health. We did mention sleep before. There are zero physiological systems in your body that are not impacted by a poor night’s sleep. Now, I don’t want to freak people out and think that one bad night of sleep is going to kill you. That’s not the case. The issue is we’re more likely to have a heart attack after a bad night’s sleep. We are more insulin resistant after a bad night’s sleep. Our cognition has slowed dramatically. We’re crankier. No system and worst of all perhaps is your immune system. Your immune system function dramatically decreases after a poor night’s sleep. So what I am trying to press upon people, you’re actively pursuing health. You’re wearing a CGM, you’re checking your HRV, you’re wearing a heart rate monitor. When you run, you’re purposely eating or not eating certain food groups. Well, you can actively manage your sleep. You don’t wait until you’re exhausted and falling to bed before you close your laptop or turn off the television. Look, I’m getting up at 05:00 a.m., I got to be in bed at 9. It’s just the way it is. I may not like it, but you have to prioritize sleep just as much as you prioritize other aspects of your approach to live longer. And then food, I think food is a really important consideration. I stay out of all rabbit holes when it comes to food. I don’t push people in any one direction too hard. As you get older, you need more protein. You need to hit at least 1.5 to 1.8 grams/kg per day. Really important. It helps to maintain that muscle mass to hold off sarcopenia and to allow you to respond to your strength training or aerobic training and build new muscle. There is a rabbit hole saying that less protein is better the mTOR inhibitor crowd, the rapamycin crowd, but that, if it’s true, is only when we’re young. And it’s not true as we head out of our into our 50s. But back to diet. Small changes can make big differences in your metabolic profile.

(Mohit): That is really cool. Dr. Howard. I think the fact that you actually mentioned that and just like you, I think we also try to stay away from a lot of rabbit holes in nutrition and try to simplify rather. I think it’s a really humbling view when you actually think about health in that way, that some of the things that we actually need to do are pretty much free and available and simple in nature and just, I think, more observation oriented than sort of like driven by a specific protocol. And of course, I think the fact that it’s not a single vector that one can optimize upon, right? Not metabolic health, not just musculoskeletal health. There’s so many aspects of aging and longevity that I think in a way, it sort of feels like your body is a mystery novel. Like you don’t know what’s the next step for you and it’s a fun thing to discover.

Absolutely. Really thank you for making time to be on the podcast. I think, of course, we are huge fans of your work in the longevity space and we continue to be inspired by your work in this space as well. We look forward to having you more often in the podcast and doing more cutting edge work with you in this space. And from the listeners of the Ultrahuman podcast, we really thank you for being here.

(Howard): My pleasure. It was nice to join you. Thank you.

Outro (Mohit): With that, I hope you now have a fairer understanding of the longevity game and this episode served as an insight from a specialist’s lens. Even if you happen to be early in your quest for longevity, I hope you can now have better clarity around what the protocols are. What’s the latest research in this space? It is important to keep in mind that our body changes as we age, so do the protocols. Wisdom is when you know about these protocols, implement them when the time is right and in the right way If you loved what you heard, don’t forget to hit Save on Spotify and Apple Podcasts and like on YouTube. Your engagement means increased visibility for keen folks like yourselves to discover The Ultrahuman Podcast. As I sign off, I would like to urge you to strive to make the most out of every day and be at the best of your health. See you soon.