Introduction Of Podcast

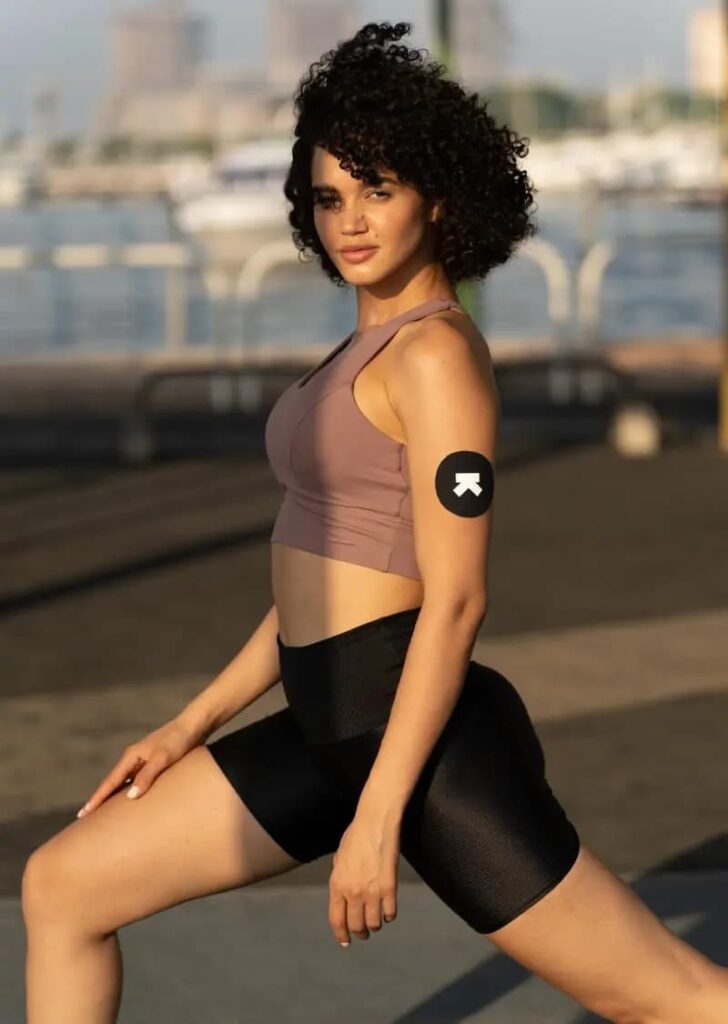

Bio-Wearables is a space that people are quite excited about. Everyone wants to get their hands on an Apple Watch, a Garmin or a Fitbit and start tracking their health. But do people really know how to read the data points? Or how can one get the most out of their bio-wearable? Elias Arjan, a prominent name in the bio-wearable space, discusses the potential of bio-wearables, some of his early experiments with biohacking, his take on nutrition and a lot more in this episode. Jump straight in!

Timestamps

(00:00 – 01:49) – Introduction

(02:20 – 05:05) – Elias’s Journey As A Biohacker

(05:23 – 12:24) – Success and Failures In Self-Experimentation

(12:25 – 21:55) – Nutrition And Its Complexity

(22:00 – 28:47) – The Future Of Medicine

(28:48 – 32:18) – View On Diets

(32:22 – 39:53) – Elias’s Favourite Biomarkers and Bio-wearables

Key Takeaways – Transcripts

Intro (Mohit): There’s a lot of chatter in the wearable technology space, a lot of excitement around devices, a number of connected wearable devices worldwide, if you look at the numbers, have actually doubled in the space of just last three years, increasing from approximately 325 million in 2016 to 722 million in 2019. And this number is expected to cross the 1 billion mark in 2022. Clearly this is skyrocketing in terms of adoption, but do we really know the true potential of these biomarkers or these bio wearables that the biomarkers that they come with? Or do we really know what really we can do with these data points? To answer these interesting questions, we are joined by Elias Arjan a pioneer in the bio wearable technology space for more than 20 years. He’s renowned for his work in health sciences, biohacking and behavioral change, with dozens of international publications in these spaces. In this episode, we find out how Elias went into biohacking and in the wearable technology space. We discussed what his earlier experiments were and what worked and what didn’t work. As you know, nutrition is an area of conflict for many, many years and for a lot of people, we ask Elias his take on nutrition. We also hover over a lot of interesting tidbits around diets, recent studies in human behavior, modern medicine, etc. We then double click on the current scenario of bio-wearables industry and how the evolution of space might look like down the line. Lastly, we ask Elias the promising biomarkers he believes in and the various bio-wearables he’s bullish on. Let’s jump right into it.

(Mohit): Hey, Elias. Hi, good to have you here. Such a pleasure to welcome you to the Ultrahuman Podcast.

(Elias): It’s great to be here. Thanks for inviting me.

Question (Mohit): So this is really cool. I’ve been looking forward to the podcast with you and the primary reasons for that is that you are a biohacker yourself and you’ve worked with bio-wearables. And as you would know, at Ultrahuman being deeply obsessed about the power of bio wearables in terms of shaping human behavior and in terms of what it can unlock for the human body. Before, of course, we talk about all of that. I would love to understand your background a little bit about your journey. What was your journey towards becoming a biohacker and getting into the world of bio-wearables?

Answer (Elias): So it’s a really long journey. So there’s a lot of different ways I’ve talked about this in different environments. But I was thinking about this preparing for the podcast. So I think I’m going to start in college for me. So I studied in business, but then when I did a biology elective, I switched to exercise science because at the time I was really becoming interested in athletics and so I started to do triathlons. I was studying exercise science and I became a personal trainer. And so at that time, basically what happened was I became obsessed just about my own performance, right? Like, how do I get better? How do I get faster? How do I improve what I’m doing? And I was starting to approach it with kind of a scientific mind. So it’s like, okay, I got to start testing different things, right? So I started testing different protocols on myself. And then what would happen as a trainer, people would come into the gym and they would ask me like, hey, I heard about this new diet, I heard about this new supplement, what do you think? Because I was an expert to them, right? And so I was like, well, I don’t know, I have to go try that. So I became this sort of radical self-experimenter way before biohacking. This is back in the 90s. This was way before the term biohacking existed. So I started conducting radical self experiments where I would literally say, okay, I’m going to try this fitness protocol for the next month or two and see what happens. I’m going to try this supplement and see what happens. And so fast forward two or three decades, right? And around several years ago, I started to realize there was a whole community of people doing this, because I’d been doing it the whole time. I’ve been doing this for decades on my own, in my own little isolated world. And then I found the world of biohacking. And what I found amazing was, to me, biohacking was very tied to the quantified self movement because the idea that not only could I hack my own biology, but I could now conduct quantified experiments on myself and start using wearables to gather data. And so really what’s been exciting to me over the last five years is we have the opportunity now that we can conduct these end of one experiments on ourselves. We have access to wearables, we even have access to at home blood testing and DNA testing and all these other things. So now we can start to really understand in our own world exactly what works for us. And so I’ve been advocating for that for the last several years now, and I’ve even gotten so far as now I’m helping other companies conduct research so that they can validate their products and their protocols and become better in the health and wellness and fitness industries.

(Mohit): Wow, that’s really cool because you mentioned quantified self, you mentioned a community of biohackers, and you mentioned that you did it in the 90s. I don’t think I even remember hearing about biohacking or anything like that in the 90s. What was very interesting is that you start experimenting on yourself, right? So what’s really cool is that the loop that you have in biohacking, right, when you talk about, let’s say when you look at healthcare generally, the loop of experimentation is very, very long. You come up with a new pill, a new therapy. It takes years and years and years before it becomes reality for millions of people or even for a few thousands. But what’s interesting is that biohacking community, it’s try fast, fail fast, learn fast. And that is really cool because you’re sort of like treating your own body as a lab, because you’re accountable to only yourself. If your health is the outcome that you want, nobody else is actually accountable, and nobody can actually buy health for you. You are the only one creating help for yourself.

(Elias): And the measurements are a lot easier, right? Because it’s like if my deadlift goes up when I try a new protocol, it’s like, it’s very clear that this thing worked, right? I don’t need somebody else to tell me that, hey, we did double blind placebo controlled clinical trial, and this improved muscle strength, it’s like, no, my deadlift went up. I know this worked for me. Now, does that work for everybody? That’s what we don’t know. And that’s when you do need those larger trials and those larger studies. But yeah, and just back to your point about the 90s. Yeah, definitely. Nobody was calling it biohacking back then. I mean, I didn’t know to call myself a biohacker. I was just doing this. So I guess I’ve always been a biohacker in that sense.

Question (Mohit): Absolutely. And one of the aspects that you mentioned, which is really cool, was one is that it can give you deep personalization in terms of who you are and what works for you, right? So if a particular method helps you reduce your resting heart rate and doesn’t work for the other person, it’s your method and you can discover your own. The other important aspect which you mentioned was experimentation. I just want to double click a little bit on that. Think about self experimentation. What are some of the ways to what are some of the things to experiment and measure? Because experimentation and measurement go hand in hand, right? We can’t experiment with what you can’t measure. So maybe your top five, your favorite experimentation methods that you would have tried over the last few years, maybe some success stories and maybe some failures as well.

Answer (Elias): Okay, that’s a good question, actually. That could go on for a while. So I think really self experimentation is essentially applying the scientific method right to yourself. And so, surprisingly, even people who call themselves biohackers don’t really understand this. And I think, to be quite honest, a lot of them aren’t doing it right. That’s why I said to me, biohacking is part of quantified self. So I’m what I call I even had a qualifier. These days, I call myself an evidence based biohacker because to me, that’s when you’re gathering the evidence right, to biohack. So really, you have different ways to gather evidence. So the two main ones that people want to think about is objective and subjective. So up until recently, most of my life, I could only really gather subjective evidence, meaning that you take a supplement, do you feel better, right? Something says it’s going to make you have higher cognition. It’s going to help you with mental clarity. That’s very hard to measure, right? So you kind of go, well, this do I feel better? Is my brain is this nootropic making me a little more clear? That’s very subjective. That’s very personal and individualized and it’s kind of based on your own opinion. Now, the challenge with anybody who conducts rigorous science, your own opinion tends to be extremely biased, right? There’s things called like placebo effect. There’s expectation effect, there’s all sorts of confounding factors. And people are actually rather bad at self reporting. So I’ve done participated in trials, you know, where people will self report that something only improved the performance, say 10%. But we’re actually looking at blood markers and it actually improved them 30%. So they were reporting much less than it actually was. The outcome was so there’s a lot of problems with subjective reporting, but it’s still something you use, so it’s not like you don’t include it. But what’s been really exciting over the last five years is now we have things like wearable technology at home, blood testing, as I mentioned before, and now you can get that objective data. So I can say, as you said before, my resting, I started a new fitness program and my resting heart rate went down 10%. Now, I would be very hard to subjectively know that, right? But my nocturnal resting heart rate on my bio wearable tells me my heart rate has gone down 10% and stayed there consistently since I started doing ice therapy, for example, right? So I started doing the cold plunges. I’m starting to do contrast therapy and I’m starting to notice these changes. So those are the two main things to keep in mind and the objective data. You know, when we’re doing research with people, we collect that in survey form, self reporting objective, again with biowarables blood tests or in lab testing, right? So I guess maybe that was the first part of the question. The second part is what experiments worked for me and what didn’t? Is that kind of what you want me to go into? I guess the bottom line there is the vast majority of things actually don’t work. I guess that’s the bad news, even if you hear that they work for other people. I would say probably, to be quite honest, my biggest experiment that was probably the most difficult for me to deal with was with around diet and nutrition. That’s a really hard one to dial in. When I was in college, I was studying, studying exercise science. I had a professor who really kind of put me on to more like plant based eating, you know, more into the vegetarian side. And I spent a lot of my life being vegetarian, leaning more towards sort of a plant based diet. And as I’ve gotten older, I’ve become now more of an animal based diet. And my performance has gone up significantly when I ate is with age. Now, diet is a very personalized thing. It ties into our belief systems, our socialization. It’s a complicated bit to get into, but diet and nutrition are something that are probably the most difficult to dial in and probably one of the most personalized. And that’s where we hope that microbiome science is going to start to give us insights there. So there’s a lot of potential that will be right now, unfortunately, is a lot of companies promising a lot on microbiome science. But I think it’s still fairly early. I think when we do unlock it, though, that’s going to be the game changing aspect that’s probably ten years from now, most health decisions will be around, oh, we analyze the microbiome. This is what we want you to do here’s the therapeutics we’re going to give you. Even medicine realizes that that’s where it’s going to go. So that was one big challenge, was that in my nutrition. That took me decades, to be quite honest. So I guess I spent a lot of time in a failed experiment there trying to figure out what worked.

(Mohit): Yeah, I think that’s one of the aspects that struck me was the fact that diet and nutrition comes out to be an area of conflict for almost everyone, right? Yeah. I heard Pavel Tsatsouline in one of his podcasts, when asked about what nutrition works for him, he said, I can’t do nutrition because it’s probably one of the most confusing things in the world. And that’s why what I only do is optimize my exercise performance. And this is somebody with like 30, 40 years of training experience. So this is somebody trying to eat better, but not finding a way back into exercise science in the last 30 years. That’s really interesting. And as you mentioned, the microbiome science.

(Elias): Yes. And for me, just to finish the thought for my story, I didn’t realize this because when you’re on a plant based diet, you’re pretty carb heavy. So now I’m on a diet where I basically am severe. I’m on a keto diet and with extremely low intermittent fasting. And I’ve trained my body to run more of ketones. I use exogenous ketones as well. And what’s been amazing is not only the physiological aspect, but the mental. The cognitive aspect is mind blowing to me. So when you dial in your nutrition, it’s not just that your body it’s not about getting a six pack. It’s actually you see the world more clearly because your brain is optimized. And so my body runs off of more like fats and proteins and extremely low carb. And I feel amazing at this. I feel better now than I ever have at any point in my life. So when you do dial it in, it’s pretty amazing what happens. And all of the inflammation that you have in your body that you don’t even realize you have kind of starts to get reduced or goes away completely. So I would say dialing in nutrition is probably the most difficult, but in something you just got to keep

at, like you said, to your point, even if you’ve been doing it for years or decades, you kind of got to keep experimenting with it because you’d be surprised when you do find the right one. Finally. You’ll kind of know it because it’s a game changing experience in your life.

(Mohit): Yeah, I think that one thing that you just mentioned about carbohydrate optimization is actually a realization that most people have very late in their life just because of culturally, especially in the Asian region, carbs being central to what we actually eat. And after years and years and years, we realize that even if you don’t get rid of carbs and sugars, but if you just optimize those carbs, right, you’ve been eating sort of like a tagged, healthy cereal bowl every morning and feeling sluggish right after. And once you replace it with something that is more stable from either a blood glucose or insulin response perspective, just changes the game. You just feel it. It just hits differently. The learning, the cognition, the ability to think clearly, all of that actually goes up. That is all the subjective feedback, but even objectively, it changes a lot in your body. And I just wanted to add one more aspect of this, what I noticed across, because we’re talking a little bit about food being a part of a cultural problem or a cultural not really a problem, but it’s driven by culture. It’s driven by what people like and not just and beliefs.

(Elias): And beliefs, right? Like, I was a vegetarian because I didn’t want to eat animals from a moral standpoint. So it’s tied into like, religion and morals and beliefs and culture. The great anthropologist Margaret Mead said it’s easier to change a person’s religion than to change their diet. That’s a pretty profound and she was considered one of the greatest anthropologists of all time. She studied all of these different cultures in the world and realized that you could even take a person and completely change their belief system, but they would still eat the same thing just because it was so ingrained in their mind and body, right? So that’s a pretty profound statement. That’s true. And it’s held up to the test of time. She said that long decades ago.

(Mohit): Well, that’s really interesting because if you just think about it, it’s natural for people to be more instinctively attached to their diet versus any other belief system. In fact, one surprise moment for myself when I was reading about traditional medicine and just with an open mind, because there’s a lot of conflict there. And people say, like, a lot of the modern world says that there is no value in traditional medicine. And a lot of traditional medicine also says that there is no value in modern medicine. And the problem is that maybe there’s a good combination that might exist, but people are sort of like at war always. One of the things I noticed was that in nutrition, in traditional nutrition, a lot of these things have changed according to what people want and not what the reality is. For example, let’s say you would have heard of Ayurveda, like, for example, in this case, the central concept of Ayurveda, and most of its texts is around the concept of living organisms. So if you’re eating something that whether it’s a vegetarian, it’s an animal, or whether it’s a plant, if it has enough, it’s called the concept of Prana. So if it is sort of like being eaten in the proximity of it, when you have actually harvested it, whether it’s an animal or a plant, which basically means that it has life force, it has living organisms, it’s not dead completely, then it’s actually pretty cool. It’s actually pretty okay. And it does not discriminate between you being a vegetarian and non vegetarian, meatatarian whatever, essentially, right? So a lot of that actually twisted and changed, but changed towards, oh, I only prescribed plant based eating, and that’s actually not true, and I’m stepping into sort of like a war zone here when I talk about this like this. But that is reality.

(Elias): It’s an incredibly controversial topic these days, but I think it’s important that we talk about it, especially one of the things that I’

sure we’ll get to at some point. But even like the continuous glucose monitoring data is showing this, right? It’s counterintuitive to me as well. I would think if I eat some cereal and grains in the morning, that would help me better than if I had, like, a stick of butter, right? But the fat, it’s like fat doesn’t make you fat. It’s so weird. You would think that fat is what makes you fat and carbs is what gives you energy, right? I mean, that’s what I even studied in school, right? In college, I studied exercise science. Carbs give you energy, and you know, fat is going to make you fat. But it’s not true, actually, because the fat gets converted into energy in the liver. And everybody in the world right now has a burnt out not everybody. Most people in Western nations have burnt out pancreases because they’re just eating too much carbs, right? And that’s why type two diabetes and obesity are an epidemic around the world. And so that’s objective results, right? That’s science. The data is in people, right? Like, the amount of carbs people are consuming has led to a global epidemic. We did not have this 30, 40 years ago. So what has changed? Well, if you look at it, we demonized fats, we demonized animal proteins, and we went into the bottom of that food pyramid, was all carbs, and look what happened. That’s science. So we have the data is in. It’s just that it’s not convenient to look at because there’s a lot of like you said, it opens up a can of worms that nobody really wants to go down. But, you know, unfortunately, I mean, I’ve been attending recently. I was at something called the Metabolic Health Summit, and they have these physicians around the world that are treating metabolic diseases with keto diets and curing. Not only just metabolic diseases, but all a host of conditions. And they’re kind of doing it on the fringe, but they’re practicing hard science, hard medicine, and it works. People will recover inflammatory diseases that don’t even seem to have anything to do with diet, right? Cancers, I mean, all sorts of things through metabolic changes. It’s pretty astounding what’s happening. So I feel like it’s worth mentioning. I mean, we don’t have to stay down this path, but it’s definitely one that I encourage anyone who’s listening to this something you need to consider for your own health, to how to dial that in.

(Mohit): Yeah, I think that’s really cool. And this reminds me of a recent conversation I had with Dr. Philip Ovadia, a few months back. Dr. Philip Ovadia is a mentor to us. He’s on a medical board, and he’s a renowned cardiologist. Wrote this book called Stay Off My Operating Table. And what he says is that it’s amazing, right? For the first few years of his life, he said, I stuck to whatever I knew or learned through medical school and everybody else. And what changed his life was actually his own health. His own health started degrading by the practices that he was prescribing to people. And he realized that, no, if I’m not able to manage my health by the practices that I prescribed to people, how are these people going to be healthy? And so what he did was he moved to a complete animal protein based diet majorly, understood his nutrition much better. We looked at his insulin spikes or glucose spikes and tried to sort of, like, figure out, what are some of these biomarkers that actually are going to help him and turned his life around and sort of, like, replicate that in his own workspace as well. But this is really cool, what you just mentioned. Actually, there exists another level that now is not the time to actually just have conflicts about our opinions, but to actually look at hard, objective data, because we don’t know what we don’t know. And maybe there are multiple layers of the science of nutrition. As we know more about microbiome and our environment, we might just discover that it’s very hard to figure out one size fits all because a large part of the world might just be okay with a different kind of diet than we have. We’ve never been this global. Just before the last 100 years, we’ve never eaten a truly global diet. And today, we almost eat everything that’s all around. So we might just discover that we might need a different microbiome environment to compensate for that.

(Elias): Right. And your microbiome is going to be different depending on what part of the world you grew up in. So you have the cultural, you have the genetic, right? So you have what is your genetic disposition from your parentage? But then even if you had parents, let’s say from let’s say you had both parents were saved from Africa, but you grew up in Massachusetts in the US, right? Your microbiome is going to be different than if you had grown up in Africa with those parents, but you still have some of that genetic memory and some of the inheritance of your parents. And there’s even things that they talked about. One of the microbiome bits that I thought was fascinating that I heard is that the baby’s microbiome actually gets converted from the mother to the infant. A huge part of the conversion happens through natural birth. So when a woman has a cesarean, the microbiome does not get set, and then the secondary level is also through being breastfed. Not to say that, but cesareans have gone up exponentially around the world is the treatment. And so there’s a lot again, these are still to be further researched, but these are things that probably have pretty profound impact that we just hadn’t thought of before. So that when you have a cesarean, you actually are depriving that infant. And again, sometimes you have to do it. So don’t get me wrong. If you had it, your mother did, or you have to do it as a woman. That we totally understand that’s not the case, but I think what we’ll have in the future is we’ll be like, oh, this baby had a cesarean. We’re going to do a microbiome transplant from the mother to the infant in the hospital before we send them home because they had a cesarean, because there’s something that happens in that. And then again, something else, that if the infant

can’t be breastfed for whatever reason, we’re going to have to do some microbiome support at that young age to help set that person’s microbiome properly. So these are things that are there is research and literature behind them. There are people conducting the studies, and it’s very promising. And it’s probably, like I said, it’s going to be part of the future of medicine once we can dial it all in.

(Mohit): That’s the most optimistic view of the future of medicine. Like, I think in all fairness, what the modern medicine, or let’s say the evolution layer of medicine has done is that it has made it more inclusive for people to have a better quality of life. So maybe 100 years back, your survival would depend on your environment, your genetics, the food you have in and around the infectious diseases that you’re exposed to. But now most people have a good shot at living or surviving through most years of life. So it does actually solve a lot for the downward or the sort of like the fallback scenario for humanity, which is essentially like how do most people survive? Even if you don’t have the genes, even if you don’t have the environment, even if you don’t have access to completely safe environment from infectious disease perspective. But even then, how do you survive? And I think what biohacking and modified self is doing is that it is saying that this to another level. It is sort of like helping the system evolve faster. Otherwise we’ll just be optimizing for people not dying, which is obviously a big problem to solve, but then it does not optimize for how do people live a better quality of life.

(Elias): Yeah, I believe we’re creating a new category because I think what we’ve had is we had, like you said, it’s synthesizing from a number of spaces. You mentioned even traditional medicine, right? And some of these traditional so modern medicine through a lot of that in the garbage, and they probably threw the baby out with the bathwater. There’s a lot of intelligence in some of these traditional ideas and then a lot of the biohacking community these days is throwing away a lot of modern medicine because they’re like, oh, well, modern medicine has become whatever corrupted, or it’s just focused on acute care and it doesn’t look at chronic disease. But again, you’re throwing out the baby with the bathwater, right? So I think we need to have a synthesis where we bring all of this together. And I think it’s a new category. We don’t really have a name for it. I personally like to call it biohacking. I’ve started to even if people don’t like that term, I said evidence based wellness is another way to look at it because it’s the idea that we’re applying this rigorous science and medical understanding because you don’t want to throw that away. I mean, to me, the scientific method is still probably the best way humanity has ever come up with to actually really understand reality, right? So don’t throw that away. So we need to use the scientific method, but we need to incorporate into the scientific method a bit of a more open mindedness, right? And not be not everything needs you know, it’s nice to have double blind, placebo controlled trials. But I’ll give you another example. We talked about the fasting. There was recently a study that came out that said they did a study in intermittent fasting. It was not a huge study. I can’t remember the exact N number, but I think it was somewhere around 50 maybe. And at the end of the study, they couldn’t find any proof that intermittent fasting had any positive effect on the individuals. So their conclusion was we couldn’t find any proof, right? But if you look around in the biohacking community or in the metabolic health community, and even just my own end of one, I mean, intermittent fasting has completely changed my life completely for the better. I mean, it’s literally transformed everything for me. And there’s literally hundreds of thousands of people that could probably attest to the same thing. So what do we do? Do we throw out all of that data and say, well, the study said intermittent fasting was inconclusive. You can’t do that. You have to look at something with a bit of a more open mind. You say, well, if this is working for people, maybe that study. Just what were the confounding factors in that study? Even the researchers admitted at the end of the study, they didn’t say intermittent fasting was useless. They just said was inconclusive. This study because they realized they went into it, like, with an open mind. They just couldn’t get the results in that study. So why did that happen? We don’t know. But we got to kind of have a more open minded conversation about this. And I think openminded conversations have become more difficult these days, but let’s try.

Question (Mohit): I think that’s a phenomenal example, right? Because probably the simplest study on intermittent fasting. And I was on this conversation a few days back where there was a debate between calorie restricted diets, glucose, insulin fasting, and then intermittent fasting, right? And the debate was largely focused on which one is the best, and everything else is a scam that was, why can’t we have an answer, which is a combination of all three? Exactly. There is energy and energy out concept that matters, but at the same time, insulin is known to be like elevated level if insulin and glucose is known to be inflammatory. So why can’t we study that in combination with calorie and calorie out and in combination with essentially the ability to look at intermittent fasting as a behavior shaper. Why isn’t behavior shaping an important aspect of our diet? If most people correct their behavior, their diet will always be fine. But it’s very hard to create your behavior, right? And probably the behavioral science is probably one of the most toughest things to change. Like, as you mentioned, it’s easier to change somebody’s religion than their diet. Which is astounding but true. Yeah, astounding but true. It’s their belief system. So that is precisely the problem, that my goal is not to defeat the other person’s view. My goal is not to defeat calorie restricted diets. My goal is to study that with an open mind and also combine it with the powers of biomarker tracking, because a lot of people can’t do calorie restricted diets as well. Like, it’s very hard for them to measure the thing and ensure that they’re eating by the sum of calories. Is there an easier method for them that can shape their behavior?

Answer (Elias): That’s just been an area of mine personally. That’s actually what I’ve been talking about lately more, because I realized a lot of people in the biohacking community are talking about, like, try intermittent fasting or try this or try so everyone’s giving you protocols or products, but no one’s talking about the underlying condition of behavioral change, right? Like, why is it so hard for most people? So you can give people a list, a to-do list of things to do for their health, but then they don’t do it, so what’s the point, right? And that’s actually been the area myself that I’ve been focusing most of my work on these days in terms of my speaking and some of the education I’ve been doing. And the advocacy is more around acknowledging the difficulty of behavioral change and then how do we actually go about sort of reprogramming our behavior? It is it’s the hardest thing to do, but this is the underlying foundation of all of this other work, right? So you gather the data and you tell people, okay, this is what makes you the healthiest person. If you change your diet to this and then what happens? They don’t do it. So who cares if you got the data, if you got the proof, if you got everything else, who cares? Because the person doesn’t change the behavior, even though you know this is exactly what’s going to make you a healthier person, right? And again, as we know throughout history, people who try a diet bounce back most of the time. So even if they do change their diet, it only lasts the second elastic band. They stretch and they’re like, oh yeah, I’ll do it for a while, and then they go back to their baseline, whatever that was, no matter how unhealthy it was. So this is the fundamental problem we have to deal with now. And that’s even where bio-wearables need to get to in the next level, right, because the current level is they’re giving data, but then they’re not changing behavior, they’re just giving the information. So this is going to be the next evolution of the entire space, I believe.

Question (Mohit): I was just getting to that as well. So bio-wearables, right? So tell me a little bit about like, what would be some of your, like, you can say the most promising biomarkers that you would have looked at, and of course the bio wearables as well, but the most promising biomarkers that maybe even both bleeding edge and cutting edge and something that you would want to watch closely.

Answer (Elias): I think right now, especially on the cutting edge there’s, a lot of the more cutting edge wearables are already getting a lot of good data. So we already have now nocturnal heart rate. Well, we don’t have core temperature. I think that’s going to be one of the next big things that somebody’s going to try to get onto some of the wrist worn wearables. Some of the big brands are trying to figure out how to get better temperature readings because even if you look at right now so the big players, the Whoops, the Ouras, they do start to give temperature, but they only give you, like, off of your baseline, but they say you’re down zero 3% of baseline, but don’t even tell you what your baseline is. So that’s not very effective, right? So I think we need to do better in temperature, but we already have resting heart rate, SPO2 respiration rate, HRV. Of course, I’ve done a lot of talks on HRV. So the heart rate variability, for those of you not familiar with it, it’s a measure of your autonomic nervous system. The relationship between sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system, a very important metric to measure number of different ways to do it. Some people do it first thing in the morning, some wearables do it throughout the entire night. Some take a reading just from a certain point in your sleep cycle and then they report your HRV metrics. And then of course, continuous glucose monitoring is completely changing the nutrition game. But here’s the thing, we now need to aggregate all of that information. So I want to know, how does this food affect not only my CGM, but my HRV and my nocturnal heart rate, right? So how do we aggregate all of that together? So now that I know that the ultimate Biowearable Master device would be something so effective in real time that if you ate a food, your HRV would drop just enough that your wearable would say, hey, your body is having an inflammatory reaction to that food. Which is an astounding idea, but it’s possible sometime in the future, probably not too distant future.

Question (Mohit): Yes, I think that’s definitely the dream that we are chasing as well with the platform. And not to talk too much about it, but I think the power of correlation is actually quite real. And metric like glucose, which is uni-dimensional, this becomes so much more powerful when combined with your activity information, your sleep cycle information. And today a lot of guesswork is actually on some of these factors. Like, for example, if my glucose baseline is off, it could be an inflammatory response. It could be a response because I’m consuming like foods with different glycemic index, or it could be because of my sleep. So how do I know that? How do I know which one actually happened more frequently, right?

Answer (Elias): And how do they relate to each other? Like you said, how does that glycemic response in that moment relate to your sleep that night? Because how does it all sort of tie together that’s I think the next phase that we’re looking at of aggregating the data. So sorry to interrupt, please go ahead.

(Mohit): Like as you said earlier, there is this subject, even though this is way more objective than just observation, but this is still a lot of objective data, that if your glucose spikes are closer to when you sleep, your REM gets disrupted. And when your REM gets disrupted, you basically have poor recovery, leading to poorer glucose response the next day. And it’s sort of like in a micro incremental way. It becomes like a downward spiral, right?

(Elias): And if you’re not getting good enough sleep, you tend to make poor decisions. So you’re going to go for that. You’re going to go for that unhealthy lunch because you didn’t sleep well. And then that unhealthy lunch is going to make you more tired and have more of a glucose response in your body. Then you’re going to get more fatigue. The next thing, you’re going to make even worse decisions, and then you have the spiral of behavior that leads to chronic disease. And that’s why we have an epidemic of chronic disease, because it’s all an infinite loop that ties to itself. So we gather the data. So now the biowearables are throwing in a ton of data. Nobody knows what to do with it. Let’s be honest. Nobody knows what to do with the data. It’s just a ton of data. People are sitting there looking at their app on their phone saying, I have no this is cool, but I don’t know what to do, right? So I think the next phase is we still can’t change behavior off of data alone. So we now need to take that data. We need to aggregate it, which is what I think is the next phase. We aggregate the data, so now we can start to create inferences, like you said, right? Your glucose spikes, you have ten glucose spikes. This day, your sleep is horrible. The next day you’re going to feel like crap, right? Okay, we’re going to advise. We’re going to prove to you now here’s why that happened. And then we have to have a behavioral modification program that says, here’s how you’re going to improve it, and that’s going to be further down the road. But once we aggregate the data, then we have to figure out how it’s going to change human behavior, and hopefully we can figure it out sooner rather than later, right? Because almost 90% of Americans are metabolically inflexible. The statistic everyone throws around is from a University of Chapel Hill study. It says 88% of Americans are metabolically inflexible. So if that’s the case, then that means literally nobody’s healthy, right? So chronic disease and metabolic inflexibility is the norm. That’s the norm, the standard. So to get out of that is going to be a lift. And I personally, that’s why I’m involved in biowearables, because I believe that once we get to this, right, so we get the data, aggregate data, and start changing behavior, then maybe we can start to turn this train around.

(Mohit): This is really cool, and I think so many golden nuggets there. But most interesting one is and the statement that you made sort of resonates pretty much with what people used to say about a famous computer scientist said this about personal computers in the 80s, is that computers throw a bunch of information at people, and people are saying, wow, this is so cool. But we don’t know what to do with this. Except when you’re a computer scientist or a mathematician. So do people really need computers, personal computers that do not everybody is flying an aircraft or doing complex calculations, right? But now, of course, computers have become ubiquitous. Obviously they’re available across our handheld sized phones or laptops or every machine. Like everything that we use has a computer built in. So I think in the biowearable space, if 80s were like, you can say 40 years back and generally it gets faster to scale and create a new category. So if we are in the 80s of biowearables, maybe it will take ten years before everybody has a biowearable on and everybody understands why are the interface that we create that this is what they need to do right now to improve their health.

(Elias): I love that analogy and that comparison. I think that’s great and I agree with you, it does happen faster and I hope it happens faster because like I said, the conditions of our society require it to do so. This has been such an amazing conversation, Elias and I got multiple goosebumps along the way, I think in this conversation and really learned a lot as well and would love to continue the dialogue and talk more about this because I think as you mentioned earlier, there are real conversations that need to be had in this space. Now, the thing to fix is can we have real objective conversations around human health and evolve this space together? So really appreciate you taking time out and of course we’ll continue this conversation and thank you for being here.

(Elias): It’s great to be here. Thanks for having me. I appreciate it. Thank you, Elias.

Outro (Mohit): We’re still very early in the entire wearable space globally. The good news is that the adoption is on the rise here or near. But the potential bad news, or it’s not really bad news, but there’s a lot to be done in terms of the interpretation of the data that’s being thrown to us. This happens with every industry. First you have the data and then you build a better interface. But with this segment, I hope you are able to gather a few insightful ways you can use a wearable or your data from a wearable much more meaningfully. If you loved what you heard, please share this episode with your friends and family, especially the wearable fans that you know of. I’m sure there are a lot of new biohackers all around. If you like the work we are doing with the Ultrahuman Podcast, please show us your support by rating and reviewing us on Spotify and Apple Podcasts and it helps us reach out to millions of people who can benefit from this. We’ll be back soon with the next one.