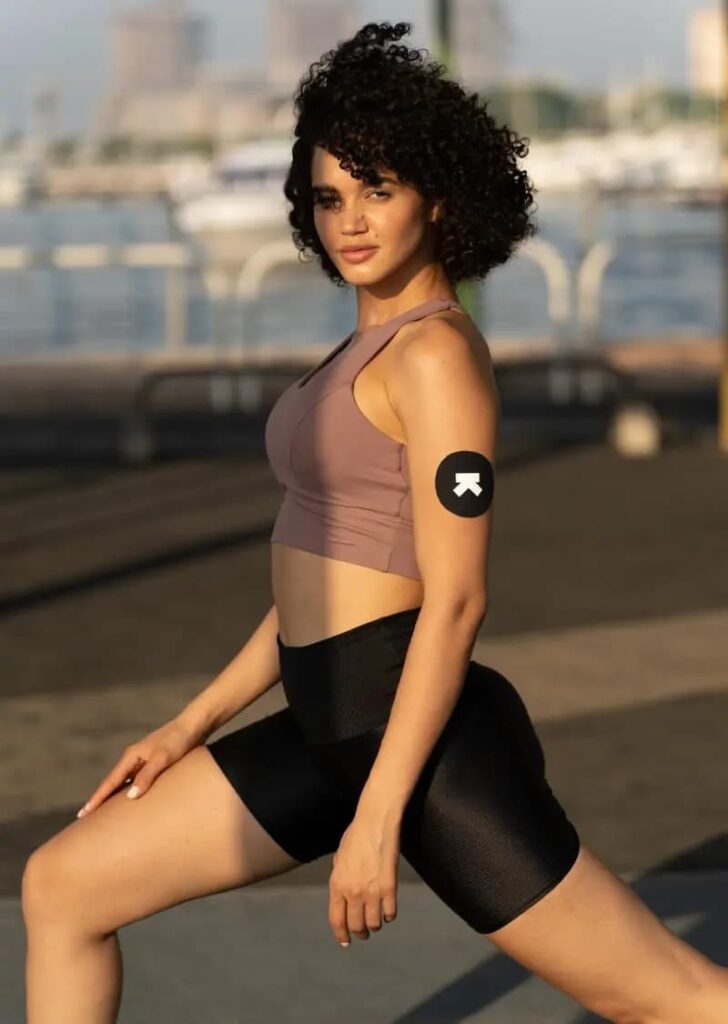

We’re thrilled to add new layers of biomarkers for you to track and optimize your lifestyle with the Ultrahuman Ring.

A cornerstone of the Ring AIR experience is heart rate variability (HRV). But what exactly is HRV?

In this episode, we are joined by Marco Altini, founder at HRV4Training, who explains what HRV is all about and how you can leverage this biomarker for a huge performance boost:

Read more: What is HRV and how can you improve it

Timestamps

(00:00 – 01:57) – Introduction

(02:13 – 04:12) – Marco’s Journey In The HRV Space

(04:42 – 09:56) – What is HRV?

(09:57 – 12:06) – HRV & Glucose

(12:11 – 13:53) – Factors That Affect HRV

(14:14 – 16:00) – HRV and Impact On Stressors

(16:45 – 20:40) – Future and Potential Of HRV Systems

(20:43 – 22:03) – About Marco’s Company – HRV4Training

(22:59 – 30:04) – Evolution of HRV In The Future

(30:07 – 32:50) – Marco’s Vision For The Space and The Top 3 Methods To Optimize HRV Biomarker

Key Takeaways – Transcripts

Intro (Mohit): So with the release of the Ultrahuman Ring and the fact that we’ve added a bunch of new biomarkers for you to track, that is like HRV, skin temperature, etc. It is only fair that we kickstart meaningful conversations around it to understand more about the potential of these biomarkers. To make this fun and interesting, we’re joined by Marco Altini.

In today’s episode, Marco is a prominent name in the HRV space. He’s the founder of HRV4Training, which is a mobile platform using advanced signal processing and data analytics to measure physiology and quantified stress, helping athletes of all levels to better balance training and lifestyle stresses to optimize performance.

So, more about Marco Altini. Marco has a background in data science and computer science engineering. He also has a specialization in high-performance coaching. In 2020, Marco took a role as a Data science advisor at Oura, working on the development of the next-generation steep staging algorithm. Safe to say he is extremely experienced in this space. If you are very new to the concept of HRV, don’t worry, this episode can serve as the perfect preface for you to understand this biomarker better. We discuss what HRV is in simplified terms, and deep dive into how different lifestyle elements, such as the environment we live in, the diets, sleep, etc. play a huge role in your HRV.

We also discuss how blood glucose and your HRV is inherently correlated and how by having a different view of this correlation, you can actually unlock more about your health. Last but not least, Marco shares what his vision in the biomarkers space is all about and what his top three ways one can get started in terms of understanding and optimizing their HRV. Let’s dig deep and find out more.

(Mohit): Thank you, Marco, for making it to this podcast. Such a pleasure to be speaking to you and finally getting a chance to pick your brains on the topic that we are so excited about.

(Marco): Thank you. Thank you for having me here.

Question (Mohit): All right, so I just want to quickly begin with a little bit about your background and would love to understand a little bit about you. So what I know is that you have a data science and a computer engineering background, and you sort of got into high-performance coaching and into health data, right, eventually. So that sounds like a fascinating story. So tell us a little bit about that.

Answer (Marco): Yeah, sure. Well, I would say nothing that I had particularly planned. I was studying computer science, and I wasn’t probably interested in many of the aspects of traditional computer science education until I had the opportunity to basically do a course called embedded systems. That was maybe 15 years ago.

It would basically mean that you start playing with sensors, right, and measure things either in the environment or on the body. And that’s what triggered my interest eventually. So the ability to measure physiology, things like at that time, maybe heart activity, brain activity, link that to stress and how that could be used then maybe to make adjustments. So it started a bit that way, and eventually I developed this technology that is present in HRV4training, which allows to measure your heart rate variability using the phone camera.

That made it easier for people to track these variables. And as I got more interested into also the physiology aspects of people using this technology, for example, typically recreational or professional athletes, then I went back to university to also study high performance coaching, and let’s say sports science. So that I could better understand. Let’s say also that aspect, and not only the technology piece but also the physiology and all these issues in practice. That’s a bit what happened, I would say in the past ten years as I tried to develop this technology and also work with people who use it in applied settings.

Question (Mohit): It sounds like a fascinating journey, but also a very early space to some extent, given the fact that variables are pretty new, the bio variables of course are very, very new and the devices that measure HRV or your nervous system etc. are very new. And somewhere along the line you mentioned, you also happen to mention about HRV. If I just look at five years back, heart rate was something that you could listen to, but literally listen about, but not as much as much as HRV, right?

HRV has become such an amazing buzzword, but would love to understand for somebody who’s worked in the hire space for so long, what does HRV really mean in simplified terms, for people who are new to this, what could unlock for human health?

Answer (Marco): Yeah, so in terms of HRV, what we refer to is the variability between heartbeats. So we are all familiar probably with heart rate and now we can measure that both at rest and during exercise. So even when you’re resting, we measure our heart rate, I think is that the variation between bits is not always the same. So even if our heart rate is about 60 beats per minute, it does not mean that there is a bit exactly every second there is always some variation in there and that is what we quantify with heart rate variability. So this variability between bits and why do we care about that? Well, the reason is that this variability is not random; it is modulated by the autonomic nervous system. And the autonomic nervous system is basically influenced by our response to stressors. So as we face a stressor, there will be a change in autonomic receptivity. We cannot measure autonomic receptivity directly, but then we can measure how the heart, and in particular heart rhythm, is impacted by these changes in the autonomic nervous system activity. So basically HRV becomes just a proxy of our response to stressors, which means that if we have for example reduced variability between bits so the heart rate gets a little more constant. That means that typically there is higher stress, while if we have increased variability, so there is more bit to bit variation which we capture with HRV measurements, that would mean that there is less stress on the body. So that is why we look into this parameter and the research has been out for maybe 50 years or longer, right? So it’s something that has been investigated for long, but the technology has been slower because it is not so easy to capture accurately this bit to bit variation. So while we can typically at least address measure heart rate easily, even with optical methods like optical sensors that we have nowadays in watches and other sensors, or in your own phone cameras and things like that, HRV is a bit more complicated because it’s more prone to artifact and issues with movement and all sorts of noise, which makes it a little more challenging. Even though in the past few years, I would say a few sensors came out that are able to capture at least address these measures accurately and are also more convenient to wear with respect to test traps that were used before. So now it’s a bit easier to capture this data and basically look at how it changes in response to different stressors that we face from sickness to training, those sorts of things that can impact resting physiology.

Question (Mohit): Right. I think the fundamental point that you mentioned, and I think you addressed that well, is the fact that the science of HRV or the metric HRV, there are so many variations out there, like in terms of if somebody is at rest versus somebody’s moving and the interpretation might not be right. So that is one challenge to solve for. And the other one that you mentioned is that I’m curious about it. Are there biological variabilities as well? Like for example, two different human beings? For someone low HRV means stress, but for the other person low HRV might not mean stress. And is there a baseline effect as well?

Answer (Marco): It’s a great point, that’s something that we also need to understand when we start looking at HRV is that it’s different from other parameters, meaning that there are really no absolute values or population ranges that we can rely on because it is very individual. So for some people it might be higher, for some it might be lower. And this is not even necessarily linked to clear aspects such as physical activity level or fitness or things like that that are tightly coupled with other markers, like even just resting heart rate. We know that fit endurance athletes, for example, have a low resting heart rate that is due to training, but does not necessarily mean that their HRV would be higher. So it’s a bit of a more difficult parameter to contextualize in that way. And that is why the only way to actually use this data in an effective way is for a person to keep track, measure daily with software that will then interpret the data only as relative changes with respect to their own data. In that way it doesn’t matter if my HRV is lower than yours, for example, because if I face a stressor then it will be suppressed with respect to my normal. And if you face a stressor, then it would be suppressed with respect to your normal. So everything is always, let’s say on aligned with respect to your own baseline and your own data, which takes some days to acquire. Otherwise we cannot really say anything from a single measurement.

(Mohit): That’s awesome.I think that’s very very well explained. So this is very curiosity driving because we see very very similar patterns, even glucose, that independently, yes, there is a baseline effect in glucose as well, that if your glucose is always out of range, then it does tell you a little bit about the state of insulin sensitivity in an individual. But even with people living in the same region, similar physiology, similar genetics, we see a lot of variation in terms of whether their glucose stays in their 60s, 70s, 80s, 90s and how much metabolic flexibility they have. And all of them almost exhibit the same type of other health parameters, similar type of energy levels. And what we’ve seen is that hence variability becomes an equally important metric, even glucose. So this is really insteresting because you mentioned that there are similarities in how you look at HRV as well.

(Marco): Yeah, for sure. I think that makes a lot of sense for many of these parameters that we measure in physiology always there is also some genetic component that will drive some of the change or relationship with the data. That is something that is not really easily explained, of course, by behavioral or environmental variable side, by definition it’s something else that we’re not really measuring and that might impact how our baseline HRV or glucose is. So all of these parameters can have sometimes a better use when analyzed a bit differently. So with respect to our own data, and that’s the technology that we have now for HRV or glucose, like what you develop is something that allows us to look at this in much greater detail with respect to what we could do before. Right, so that opens, I think, a lot of different opportunities for people to better manage their health. Not only of course in the context of training and things like that, but just general health.

Question (Mohit): Wow, I think that’s very well summarized. And I said wow because this is a very nice rabbit hole. This brings me to an interesting point around what you already said, that all environmental factors, like many environmental factors, affect your HRV. Obviously your stress, sleep, activity levels, do environmental factors, things like pollution, the quality of water, your state of immunity, do those factors affect your HRV as well? And I’m linking this back to maybe your state of insulin sensitivity and even glucose. Have you been able to see some correlations there too?

Answer (Marco): Yeah, for sure. All of these factors impact us, right? So some are the environment around us, some is our behavior in terms of anything from diet to physical activity to sleep. And then these parameters are also often responding similarly to stressors. So if we look at glucose, we often look at it in the context of our diet, for example, of how we respond to different foods and things like that. But that response will also change based on stress, right? So it could be that there are phases and periods in which, for example, we are under higher stress, our HRV is suppressed, and our glucose will also respond differently. Maybe it will stay elevated for longer in response to certain types of foods. There’s something I had seen also in the past, even in my own data, when measuring both at the same time, the glucose response was worse in periods in which HRV was suppressed and stress was higher, as all of these processes are somewhat linked. Right? So it’s not isolated systems. I think it’s really interesting to look at both variables as they give us different perspectives on what is going on in the body.

Question (Mohit): So you mentioned that Duko’s baseline is usually up and there’s lack of recovery, right? Essentially because probably you become more insulin resistant, would stay elevated longer. Right. So your glucose disposal skills of your insulin system sort of like go away, but temporarily. Does the reverse also happen? Like basically if there is a stressor, right? And because of that my HRV dips for some time, does it have an impact on, let’s say, temporarily making me insulin resistant to some extent, like even a short bout of stress, maybe a very stressful meeting?

Answer (Marco): Yeah, it could totally be even. I think we see, for example, even in response to very intense exercise, right? High intensity exercise is an acute stressor. So it’s not some more chronic stressors that we face slowly over time. It’s very acute and we know that it creates more imbalances in the group of response. So we have a suboptimal response there. The HRV is suppressed acutely for longer. So we have an acute negative response to that stressor that we see in both signals, even though we might have in the long run some improvements also in both parameters. I think it’s always challenging to then see how the acute response might turn into a different chronic one. These typical soft exercise, right? We stress the body that is supposedly negative at times, but then this acute stressor, when we do it at the right frequency and intensity for us without doing it too much, then it will also lead to improvements in health and fitness. We always need to think about the two aspects. But acutely, it’s easier to analyze the responses, right. Because it just takes less time. So we can easily see the disruptions both in autonomic activity and I think in local responses.

Question (Mohit): So what you’re saying is essentially because these processes are so related, one system of physiology will obviously have an impact on the other one. And because the human physiology is interconnected across various such factors, you will see correlation or reverse correlation, many of these factors. Does that also mean that if we are potentially able to capture HRV accurately in real time, like today, there are a lot of non-continuous systems, essentially. So I wear a Whoop myself, I’ve been wearing Oura, and I get to some extent interesting insights about my sleep quality, my state of recovery, my readiness score, etcetera, etcetera. But potentially, let’s say theoretically we have a real time HRV system. So a machine that tells me what my real time HRV is an accurate way, and let’s say the interpretation is also quite accurate. Whether it is telling us that I’m becoming more parasympathetic and sympathetic, is there a possibility that let’s say I consume a high inflammation food and that gets my system to become sympathetic suddenly. In the future, you think that such systems will be possible?

Answer (Marco): So that’s a really good question. I would say that it depends a bit what you’re interested in. Meaning that sometimes I still think that especially when it comes to HRV, less is more. Meaning that if you measure at the right time, then you get a really good snapshot of your resting physiology and now you are responding to the important stressors in your life, right? So if you measure in the night or first thing in the morning, then you capture this overall stress on your body and that allows you to make meaningful changes to see if everything is going according to plans, meaning everything is stable, or if there are suppressions, because maybe there is a stronger stressor or something. We’re not dealing with property well. If we start to look at HRV at the very fine range scale, then there will be continuous suppressions because that is just how the autonomic nervous system works. And many of those are irrelevant. For example, if I’m just talking, then it will be suppressed. But if I’m eating it will be suppressed. Or if I do any sort of light physical activity than just walking around, it will be suppressed. But all of these things are good. It’s, you know, socializing is good and then moving is good, eating is good. It’s just that the naive interpretation is that there is a suppression and therefore typically lower HRV is associated to something negative. But that is not necessarily the case. It’s just all transitory stressors that do not have a negative impact on us, on our health. So we need to be careful there not to read too much into this information and to maybe take a step back and to look really at the bigger picture. Because if the stressors that you face during the day are impacting you negatively, then it will also be shown in your night data or in your morning data because then they will become stressors that are not just short and transitory, but they will become more meaningful stressors that impact your health. So I think the snapshot is still really the ideal way to go about this. And it can be interesting to look at something very specific, as you mentioned, maybe a very specific type of food. And you want to look at how your body responds before and after and in comparison to another food. Or we can do that sometimes also with exercise to make sure that our exercise is at the right intensity. For example, it’s not too hard. Then we could also look at HRV before and after. We expect that it bounces back very quickly if we were working at a low intensity and otherwise it stays suppressed for much longer. So there are applications of HRV outside, let’s say, assessing baseline resting physiology and how you respond to overall stress. But at the same time I think the continuous monitoring is not easy because anything we do will have an impact and often this is just due to transitory stressors that might not be relevant. It’s a bit different from, I would say, what you do with glucose monitoring where the continuous data is really helpful because it helps you in a way that you see how your body responds and how you can impact it. While autonomic activity is a bit different in my opinion.

(Mohit): Yeah, I think in potentially in autonomic activities the context is probably more important than the main, equally important as much as the stream of data.

(Marco): That is exactly the point, context is really important. It is really hard to have when you look at all the data. If you were to measure it continuously, that’s a great statement.

Question (Mohit): And tell us a little bit about the HRV4training company that you’re building and would love to know more about the product and the vision there.

Answer (Marco): Yeah, for sure. So the idea is to make it a bit simpler to measure and viability also without requiring any wearables

So we have a technology where you can measure with your phone camera on Android or iPhone and then basically the idea that you measure your HRV first thing in the morning at rest, that is typically an ideal time to measure this baseline physiological stress that I was talking about. And then as you capture that every day in the same routine, let’s say in the morning, then the tool learns what is your normal HRV and then it starts to understand when deviations from your normal are meaningful. For example, your HRV today is suppressed with respect to your normal values and that means there is more stress on your body and it might be a good idea to make some adjustments and try to give priority for recovery or lower intensity exercise or any other recovery practices, let’s say. And then basically by making these adjustments, trying to, in the longer term avoid basically periods of chronic stress that would lead to sub optimal health and performance.

Question (Mohit): So this is if we look at the pool of biomarkers out there, right? And as we know, autonomic nervous system reacts to almost every physiological activity, whether it’s inflammation, stress or any other movement or anything like that, right? The metabolic system, especially glucose metabolism, is also fairly sensitive because you see almost instantly you see the impact on how any activity, whether it’s a stressor or movement, ends up moving your glucose values. And even there, in many cases, context is actually quite key. Like for example, your activity spike versus your food spike. So the activity spikes are not necessarily the ones that you should be optimizing, given that it’s your body’s natural glycoenogenesis or gluconeogeneis’s response. But what are some of the other since you’re in the space and you spoke with HRV for training, how do you think about evolving the product to actually add more? Do you think about adding more biomarkers or actually going deeper into the HRV science? Which one of these would be your roadmap? So that’s one thing I was very curious about. The second thing is whatever you can share around this, what is the science behind using a phone camera and measuring the heart rate variability values? It’s really fascinating.

Answer (Marco): Yeah, of course. Thank you. So in terms of what to do in the future, I think that so far we got a lot better at measuring these variables. Right? So we’re talking before the technology got a lot better. You mentioned some of the wearables you’ve had that make it a lot easier. You don’t have to do anything, it’s just good to sleep. And they are measuring typically pretty good quality heart rate and HRV because there is no movement during the night. Then we can use apps like ours where you measure the same things using the phone cameras. Again, there is to capture high quality data with respect to even just ten years ago where you needed straps or a bit before you needed to go to a lab and use an ECG, and that would obviously make it impossible to measure. Every day this kind of buggy was now we got better at measuring. But we don’t know that much of how we can influence the data so that it leads to better values or better health or better performance. So our ability to influence it is not that good and we don’t know that much. And now that we can measure it more easily, I think it’s easier also to study how we can impact it. And some aspects, for example, could be linked to anything. That is practices that try to target parasympathetic activity from yoga or mindfulness or deep breathing or anything that basically involves certain forms of breathing impact parasympathetic activity acutely, as you do it. But the more, let’s say, difficult question to answer is if that also leads to a change over time that is sustained in your baseline physiology. So I think that those aspects are what we are looking into and interested in right now to see if there is a way that you can reliably try to basically change the way the data responds to different stressors or the way your data changes over time with practices like this. So that is one of the things you’re looking into that I think we will learn more over the next years that we did in the past. Then in terms of the technology. But the technology is actually not so complicated. It’s similar to what we have in wearable sensors today that use optical technology. So typically Wearables have some LEDs, some light that we can actually see. For example, typically they use green light. Some sensors like the Oura Ring uses infrared so that one we cannot see, but still they will use some form of light and then flash it through the skin and then add some other sensor to detect these changes in light absorption. When blood is flowing, obviously blood is flowing at the finger or the wrist when the heart is beating. So that information is related to heart rate variability in a way that you can simply see the change in blood volume through the capillaries using either a phone camera or dedicated sensor like wearables, and then get that information to reconstruct the bit to bit variation that you have in variability, so that you can capture that information without basically measuring the reference. That would be the electrical activity of the heart.

(Mohit): This is really fascinating because what you did really is you converted what was erstwhile hardware into software capability, right? Technically it’s still hardware capability, but it’s the hardware that everybody has access to in the world and potentially a billion people in the world could essentially provide you the data and the patterns that probably would turn out to be the biggest clinical trial, maybe not the clinical trial, but biggest observational study ever done in human health in the world in terms of many opportunities.

(Marco): Even in the context of sports science, typically studies are very small. There is maybe often less than ten people that are analyzed with respect to how their training changes, their physiology and things like that while using the platform. Last year we published a study, for example, looking at these changes in response to training as well as sickness, alcohol intake and the menstrual cycle in about 30,000 people. So it’s a lot more interesting than to look at these patterns and see how they change also across, for example, different age groups. Right? Because most of the research may be as a very small pool of people and they are similar age, typically young. But we can start looking at how things change also in stress responses for people that are 20, as well as people that are 70 or so.

(Mohit): Yeah. So the data seems very fascinating given the fact that it has the ability to contextualize or make health personal for almost everyone. And it only gets better from there because the fact that once you have enough data, you will be able to derive patterns around stress and environment like the system could essentially. Right, so the fundamental blockage in the system, which is how many humans have you tested? This one just goes away with the platform like this or even with smart wearables, because instead of doing a clinical trial, you could start doing observation studies and to understand what it is.

(Marco): Yeah, exactly. You can always try to also recruit for studies through the platform and then work together to try to basically answer research questions and see if we can understand better certain patterns that are maybe not clear from smaller studies that were done in more controlled settings. There are, of course always limitations when we do these things in real life, so to speak. Right, so there is no other site, the data sometimes could be lower quality. So it’s important to have ways to capture that, to understand when signals are optimal, when they are not, something that we try to focus on a lot, even reporting it back to the user. So when you use the platform and you take a measurement, you will get also cigarette quality measurements that are typically not reported by wearable, that are always, let’s say, pretending that your data is always perfect. But we know it’s just not the case, right? We know that heart rate with movement of the breeze is often inaccurate. So it’s important, I think, to try to be more transparent on these kind of things so that the data can be trusted also for research purposes, both internally, but also for universities and anyone else that is using the tools for their research.

Question (Mohit): Well, Marco this has been really insightful. I have two more questions for you. Obviously, like pause for the podcast, but I think the first question that I have for you, just general curiosity about your view for the space, your vision about the biomarker space overall, not just HRV. Do you have aspirations to get into more biomarkers? And what would be your view for the space? Essentially, right? So that would be one large question that your Aspiration plus what’s your vision for the space? And I would love to understand just to complete what would be your to three methods to optimize the HRV biomarkers. Yeah.

Answer (Marco): So in terms of other biomarkers, I think we will look at a bit on the available technologies. Normally we try to focus on what we do best, which is HRV measurement. But we also talked before how these measurements can really be coupled with others to better understand even the stress response. Like we said, with glucose, for example, it’s not only reacting to what we are eating, right? It’s reacting to our physical activity, but it’s also reacting to stress and the stresses we face. So integrating with multiple signals could be another way to try to better understand the body’s response to stress. Similarly, other sensors are being developed try to look at things like hydration, maybe lactate, all sorts of things that we cannot now measure continuously and in ways that are non-obstrusive. So hopefully, as the technologies keep evolving, like they evolved a lot in the past ten years, we will be able to look at more of these signals and better understand stress responses and the impact of behavior on what we could call health markers that are all of these parameters and how they change in response to stress. That would be probably what I’d like to see in the next years. In terms of how to keep basic your HRV in check, I would say really the basic exercise, low intensity aerobic exercise, maybe with some level of higher intensity exercise more occasionally, and then trying to have a good sleep routine. Apart from sleep and exercise, I would say diet at that point. Also trying to eat healthy foods, real foods, and that should lead to a more stable or improved HRV for most people. On top of that, there’s always things that we could try, like the ones that I mentioned earlier in terms of mindfulness or deep breathing practice that I think are interesting to explore but less clear in terms of the impact on resting physiology.

(Mohit): Wow. Well, Marco, this has been super inspiring and I learned a lot and I’m sure our listeners as well. This is a super fascinating space. There are so many discoveries to be made here and I think the work that you are doing in this space is actually moving the world forward and helping us unlock both human performance as well as decode human health for billions of people out there. So this is going to be like the work that actually changes the world of medicine and health tech forever, right? I mean, this is more platform work, something that will survive forever and the science will you’re essentially helping the science improve and evolve at a much faster rate. So, it’s a pleasure speaking to you and would love to stay in touch, of course, talk more about what we are doing on the art platform as well, and along the way find out ways to partner and collectively build or bring impact to the space.

(Marco): For sure. Thank you so much and for your words. It’s been a pleasure to meet you and to be on the podcast and all the best for your work in the meantime.

(Mohit): Thank you, Marco.

Outro (Mohit): So I hope with that you are able to understand the basics of HRV and why is it important for us to track and optimize this biomarker. If you have any questions around this, please feel free to start a conversation by tagging us at @ultrahumanHQ on Instagram and Twitter. We’re here to talk about this and help you have more clarity about HRV and other biomarkers. We’ll have more discussions around the topic with multiple experts as we go along this way. Make sure you’re subscribed to the Ultrahuman Podcast. See you soon with the next one.