Elite athletes often have resting heart rates that seem abnormally low by general standards, and there are some very famous examples.

Professional athletes’ heart rates often dip into the 30s or even the high 20 bpm. It’s a sign of extreme cardiovascular efficiency. Years of high-volume endurance training strengthen the heart, allowing it to pump more blood with each beat and requiring fewer beats overall.

In contrast, a high resting heart rate, typically defined as above 100 bpm, can be a marker of chronic stress, poor fitness, or underlying health conditions such as hypertension or heart failure. For pro athletes, low is normal and often optimal.

Highlights

- Endurance sports like running, cycling, and triathlon are associated with significantly lower resting heart rates. This is due to structural and functional adaptations in the heart that develop with consistent training.

- One major adaptation is cardiac remodeling, where the left ventricle increases in size and muscular strength. This allows the heart to pump a larger volume of blood with each beat, meaning fewer beats are needed to supply the body with oxygen.

- As a result, endurance athletes typically show resting heart rates between 30–60 bpm, reflecting improved cardiovascular efficiency and lower physiological stress.

Famous athlete’s resting heart rate:

- Michael Phelps ~38 bpm

- Miguel Indurain 28 bpm

- Lance Armstrong 32–34 bpm

- Usain Bolt ~33 bpm

- Martin Fourcade ~25 bpm*

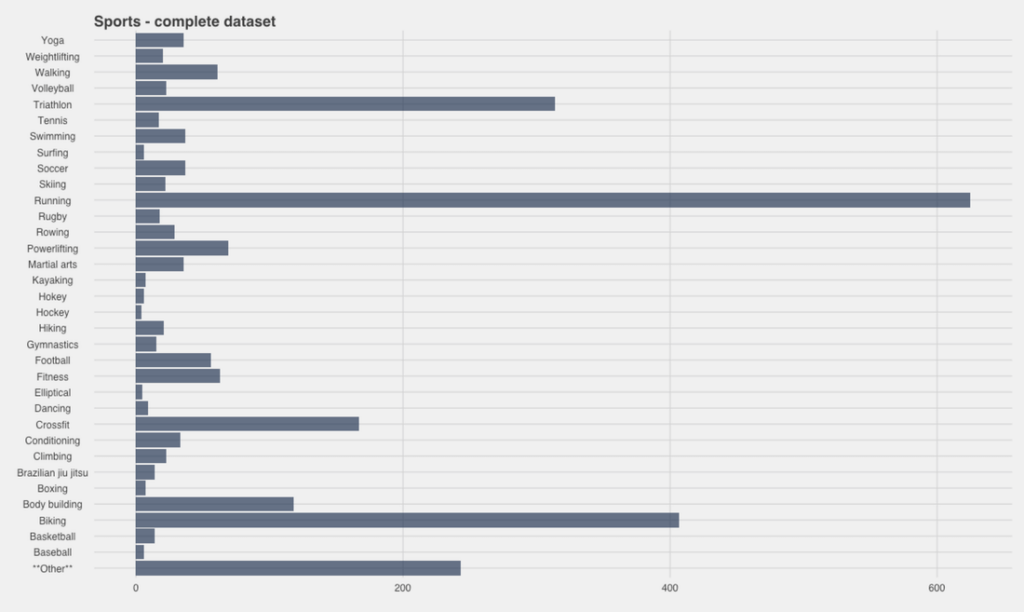

Athletes’ RHR for different sports

The long-endurance sports of running, cycling, triathlon, etc., have lower RHR as the heart itself increases in size and strength. The ability to pump blood is more efficient and requires fewer heartbeats to supply blood to the entire body.

This is predominantly observed when athletes train in different heart-rate zones and intensities to build capacity. Thus, lower-intensity zones would require a lower heart rate to meet the demands of the exercise. This, therefore, increases the endurance capacity of the individual.

Why do athletes have such low resting heart rates?

Due to constant training, especially endurance training, an athlete’s heart undergoes certain positive changes.

The muscle of the heart, especially the left ventricle, thickens; this increases the ejection of oxygenated blood from the heart around the body and thereby reduces the heart rate. These are some normal adaptive changes in structure and function that help the athlete perform better, considering the unique demands posed by the sport.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), however, which is a clinical condition, is fatal and can cause sudden cardiac arrest.

Dilated cardiomyopathy is when the chambers of the heart enlarge to store and pump more blood out while HCM involves increased thickness of the wall and decreased size of the chamber. Due to endurance training, certain adaptations facilitate an increase in the capacity of the heart to pump more blood. The adaptation includes an increase in the size of the left ventricle as well as an increase in the muscle strength to pump blood more efficiently.

Why low RHR isn’t always good

It is important to distinguish between an athlete’s heart and HCM. One is an adaptation, while the other is a life-threatening genetic disorder.

A primary distinguishing factor is the measurement of the wall thickness. Anything over 13 mm is considered a pathological change. With increased wall thickness, the space in the chamber reduces and thereby reducing the amount of blood pumped out of the heart.

Conclusion

Sports need a high level of fitness and recovery. Training intensity and progressions have a huge impact on the body (structurally and functionally).

Endurance training increases fitness by decreasing heart rate and stress, and improving efficiency in blood flow. It is normal to have a lower RHR in athletes (30–60 bpm). However, it is crucial to check for any abnormalities through regular check-ups to prevent any unnoticed disorders or deaths.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are for general information and educational purposes only. It neither provides any medical advice nor intends to substitute professional medical opinion on the treatment, diagnosis, prevention or alleviation of any disease, disorder or disability. Always consult with your doctor or qualified healthcare professional about your health condition and/or concerns before undertaking a new healthcare regimen, including making any dietary or lifestyle changes.

References

- Rest heart rate and life expectancy.

- Effects of Exercise on the Resting Heart Rate: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Interventional Studies.

- Assessment of Autonomic Function in Cardiovascular Disease: Physiological Basis and Prognostic Implications.

- Resting heart rate: what is normal?

- Resting heart rate and the risk of hypertension and heart failure.