When you think about building a better body, it is likely that you imagine yourself in a hardcore training montage, at the end of which you appear resplendent in your perfect form. This only becomes a problem when it translates into you overdoing it at the gym, this can lead to overtraining, ego lifting, permanent injuries, and the eventual drop in motivation. Heart rate zone training brings your attention back to where it should be—the present state of your body. One of the most personalized styles of training, heart rate zones teaches you where you need to improve, and what it would take for you to reach your maximum intensity. And it all starts at Zone 2.

Highlights

- Some athletes measure their exertion across a scale of 3 zones, some use a scale of 5, while some even go up to 10,

- Through long-term aerobic training, your heart can improve its ability to pump more blood per beat (cardiac output), and the blood vessels surrounding your muscles can increase in size (vasodilation),

- Metabolic flexibility is the body’s ability to process fuel from either source of energy—fat or glucose.

What are heart rate zones?

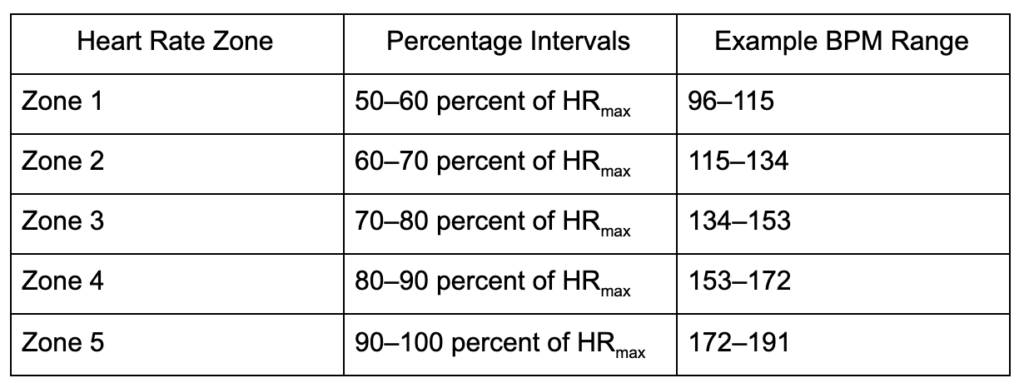

Heart rate zones are percentage intervals of your maximum heart rate. These zones, or intervals, are used to determine your exertion during a workout. Too high a heart rate? You’re probably in a higher zone. Is heart rate too low? You’re likely in a lower zone.

How many zones are there?

It varies. Some athletes measure their exertion across a scale of 3 zones, some use a scale of 5, while some even go up to 10. The higher the number of zones, the more granular the measurements. While many factors besides an athlete’s experience affect the chosen scale, it is popular to go with the scale of 5. It is specific enough to let you feel the difference when you switch between zones, but not too specific that it diverts your focus from the workout.

Heart rate is measured in BPM (beats per minute). To determine our heart rate zones, we first start by measuring our ‘maximum’ heart rate (HRmax). The most accurate way to do this is through laboratory testing, but you could also get an estimate with either an exercise, or a formula.

A popular formula supported by the HUNT Fitness Study for men:

HRmax = [211] – (0.64)*(age)

So, for a man aged 32, who has no history of heart disease and isn’t on any heart medications, the maximum heart rate will be calculated in the following manner: HRmax = [211 – (0.64)*(32)] = 191 BPM

Traditional formulae like the one above have proven to overestimate HRmax in women.

The following formula, based on a women-specific study conducted by Dr Martha Gulati,

A popular formula supported by the HUNT Fitness Study for women:

HRmax = [206] – (0.88)*(age)

So, for a woman aged 32, who has no history of heart disease and isn’t on any heart medications, the maximum heart rate will be calculated in the following manner: HRmax = [206 – (0.88)*(32)] = 178 BPM. Once you have your HRmax, you can start creating your zones. Here are the percentage intervals for each of the 5 zones, based on the above HRmax example of a 32-year-old man:

During your workouts, your body can experience heart rates that hit all of these five zones—some even more than once. These zones are named by different colours like blue, green, yellow, orange and red heat rate zone colours. But you don’t always need a heart monitor to notice this. Generally speaking, you can apply the ‘talk test’ to measure the relative intensity between zones. A talk test lets you know if you’re exercising easy or hard without any equipment. If you can sing during your workout, you’re going too easy, and if you can barely say a word, you’re going too hard. The higher you go up the scale, the harder it will be to speak.

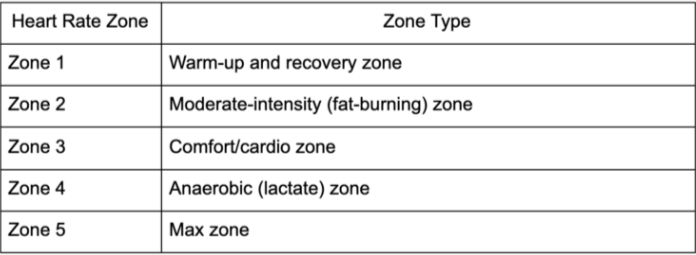

Breakdown of the Zone Types

Each zone plays an important role in your fitness. The term ‘aerobic’ means ‘with oxygen, and the term ‘anaerobic’ means ‘without oxygen’.

- Zones 1 – 3 rely more on aerobic energy systems.

- Zones 3 – 5 rely more on the anaerobic.

Through long-term aerobic training, your heart can improve its ability to pump more blood per beat (cardiac output), and the blood vessels surrounding your muscles can increase in size (vasodilation). These cardiac benefits go a long way towards improving your performance and longevity. Anaerobic zones, on the other hand, help your body increase muscle mass, improve strength, and process lactic acid. Lactic acid is the byproduct of strenuous anaerobic activity and contributes to the feeling of soreness after a workout. Each of these benefits depends on your body’s fitness as a whole, and can be targeted through zone training.

A general idea of the activities you can do in the 5 Zones

Heart Rate Zone 1

Where you do your warm-up routine or cool down during interval training. It’s a great zone for getting your heart rate up through dynamic stretches before a workout.

Heart Rate Zone 2

Where most of your energy needs are coming from fat. Low-intensity workouts like light jogging or exercises using low-resistance bands fit well in this zone and help you build a strong aerobic base to recover from.

Heart Rate Zone 3

Where you might first start to break a sweat and feel the intensity of your exercise, without feeling the pain. The tendency to overtrain in this relatively comfortable and ‘rewarding’ area is the main reason why some trainers recommend skipping this zone—though, when practised in moderation it can provide aerobic benefits like an increase in cardiac output and in the size of your blood vessels.

Heart Rate Zone 4

The anaerobic zone, where your breathing can become laboured and you begin to feel the ‘burn’ from your exercise. Most of your energy needs are coming from the breakdown of carbohydrates, which releases lactic acid into your bloodstream. Zone 4 exercises include high-intensity training like boxing, medicine-ball slams and heavy weightlifting.

Heart Rate Zone 5

Where you go all out. You will usually last in this zone for about 15–60 seconds at a time, and the majority of your energy will be derived from fast-burning carbohydrates or simple carbs. Exercising in Zones 4 and 5 can be very stressful for the body, but it can also help improve your body’s lactate threshold (i.e. improving the rate at which your body processes lactic acid)

Remember, a heart rate zone is just a percentage interval of one’s maximum heart rate. So, no matter how many zones your workout buddy or your favourite athlete uses, just knowing the percentage interval of their zone can help you understand and compare. For example, a ‘low-intensity aerobic’ workout would be deemed ‘Zone 1’ if there are a total of 3 zones. But it would be the same as ‘Zone 2’ if there are a total of 5 zones.

Focusing heavily on just one or two of the zones will mean missing out on the advantages of the rest. Your fitness goals, however, will remain the true dictators of the zones you pick. Higher zones help increase your total calorie expenditure and therefore your weight loss. But they also carry the risk of inefficient metabolism, overtraining, and injury.

Zone 2 provides the bulk of aerobic benefits for longevity and is key to building your endurance, efficiency, and performance. It is interesting to note here that many endurance athletes spend over 70 percent of their training in Zone 2. Incorporating a mix of different zones will help you optimize your metabolism and improve the efficiency of the energy systems that drive your health and body composition. The science behind the energy systems supporting these heart rate zones is how we understand important factors like aerobic threshold, mitochondrial efficiency, Zone 2 training, and more.

What is Zone 2 heart rate training?

Zone 2 exercises are steady, slow-paced workouts performed between easy to moderate levels of intensity. Think of a light swim, a brisk walk or a bike ride— anything that keeps your heart rate between 60–70 percent of your HR max. It is common to feel like you’re not working out hard enough— that’s part of the charm. The health benefits of such aerobic training are many and are foundational to your performance. Right from the point of energy supply, training in Zone 2 allows your body to burn fat as a fuel source instead of relying on energy drawn from carbohydrates.

Metabolic flexibility is the body’s ability to process fuel from either source of energy—fat or glucose. This not only helps you lose weight but also helps your body build an aerobic base from which you can begin to improve your performance. Building an aerobic base means improving your body’s capacity to generate energy using oxygen. This improves your aerobic fitness, which is why it helps you exert your maximum power during high-intensity training, and also lets you recover faster after you’ve maxed out.

Have you ever run full-sprint for 10 seconds, then ended up clutching your sides in pain, gasping for air, and altogether collapsing for hours? That was your body recovering from a Zone 4 or Zone 5 physical exertion. Training at a high intensity without a strong aerobic base means that post-workout you’ll be exhausted for longer and spend more time recovering. With an aerobic base, you recover faster from high-intensity interval training (or HIIT), while also lowering the risk of injuries and fatigue. It is also common to eventually start going for longer Zone 2 workouts, thereby increasing your total calorie expenditure through these safer, low-intensity exercises.

‘Long slow distance training’ (popularly referred to as LSD training) is one example of building aerobic endurance. Endurance cannot be improved without supplying the increasing amounts of oxygen demanded by your muscles. Sustained efforts over long distances, like in LSD training, help improve your aerobic capacity by maximizing your body’s utilization of oxygen. This is also known as improving your ‘peak oxygen uptake’, or your VO2 max.

Since Zone 2 training involves exercising at the peak of one’s aerobic threshold, it also brings with it the many cardiovascular benefits of endurance training, like a lower resting heart rate, stronger heart muscles as well as improved lung function, and stronger ligaments. This lays the groundwork for your performance and longevity. It is with consistent exercise in Zone 2 that you run slow, to run fast.

How does Zone 2 Training help improve Performance and Longevity?

The energy systems of your body are like engines that generate energy, and your body uses this energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) molecules. At any point, your body is burning both fat and glucose as fuel to supply its energy (ATP) needs. But all fuels aren’t burned in equal amounts. The fuel of choice depends on a variety of factors, a primary one being the intensity of your exertion, i.e. whether it is low or high.

During low-intensity exercises, your body has plenty of oxygen and isn’t required to produce a large amount of force. But during high-intensity workouts, your body is noticeably low on oxygen and is tasked with producing massive amounts of force at higher speeds. Think back to a time when you last went for a run. You likely started jogging slow and were breathing easy for a few minutes before you started running hard and feeling out of breath.

This is a great example of your energy and muscle systems at work. While going slow, you were possibly closer to Zone 2, and your muscles were able to function using the oxygen supplied by your breathing. Breathing also helps in glucose control. But when you started running hard, your muscles demanded greater amounts of oxygen, which left you noticeably out of breath. You were probably still able to go for about 10–15 seconds before you felt tired and stopped.

Do muscles only work in the presence of oxygen?

No. Your body has more than one type of fuel, more than one type of energy system, and more than one type of muscle. Different muscles use different types of energy systems to perform an activity. And different energy systems use different types of fuel depending on the intensity of the activity. Low-intensity exercise utilizes type I muscles, which are also known as the ‘slow-twitch’ muscles (or ‘red fibres’ due to their composition and blood supply).

These are smaller and produce lower amounts of force. High-intensity exercises use type II muscles, which are also known as the ‘fast-twitch’ muscles (or ‘white fibres’). White fibres are larger and produce greater amounts of force. Both these muscle types use different types of energy systems. One metabolizes fat, while the other metabolizes carbohydrates.

Can you guess which one burns fat?

Mitochondria are the powerhouse of the cell. Your red slow-twitch muscle fibres contain a larger amount of mitochondria and myoglobin and are surrounded by a greater number of capillaries. This creates the perfect environment for muscles to be fuelled through the oxidation of fat. Mitochondria present in these muscle fibres break down the fat in our body to release energy in the presence of oxygen. This process is called ‘mitochondrial respiration’, and the energy system used here is called the oxidative system.

Exercising in Zone 2 improves the efficiency and the number of mitochondria in your body. It increases the network of the capillaries surrounding your muscles, which helps improve your VO2 max and oxygen supply. It also improves your body’s metabolic flexibility, thereby helping it utilize the body’s fat reserves to produce energy, instead of tapping into the limited carbohydrate-based reserves. Fat burns in the presence of oxygen, which is why Zone 2 exercises are also known as aerobic exercises and are used to build an aerobic base.

When you push your exercise and heart rate above the intensity of Zone 2, you begin to enter the anaerobic zone. Here, your fast-twitch white muscle fibres are activated, and your anaerobic energy systems kick in to supply the energy. To do so, your body uses an energy system called glycolysis. Your body breaks down the carbohydrate-rich food you eat into molecules called glucose. These glucose molecules are stored in your liver and muscles in the form of glycogen.

During high-intensity anaerobic exercises, your body’s glycogen stores are ultimately broken down into pyruvate and energy, where the latter is released in the form of ATP. This energy is released anaerobically and only lasts for a short period of time. Pyruvic acid, a by-product of glycogen breakdown, further ferments into lactic acid, which plays a significant role in the ‘burn’ you feel at the end of a strenuous workout. This is partially why glycolysis is also referred to as the ‘anaerobic lactic system’.

Lactic acid is further broken down into lactate and hydrogen ions; it is these ions that are responsible for the burn. Lactate, amazingly, is another fuel source that can be burned in the presence of oxygen by a transporter protein called MCT-1. Zone 2 exercises help your body create more of this protein, thereby helping clear your blood of excessive lactate by shuttling it into the mitochondria for energy production.

Which energy system is better?

Glycolysis produces 2 ATP molecules from one molecule of glucose. It is a fast system but only provides energy for up to 2 minutes during a high-intensity workout. Naturally, the glycogen stores in the muscles are limited and are exhausted very quickly. This is why you can’t run at Zone 4+ levels for longer than a few seconds.

Oxidation, on the other hand, is a slower system, but it produces over 100 ATP molecules from one molecule of fatty acid and provides energy for several hours of low-to-moderate-intensity workouts. This is why you feel like you can ‘go all day’ at a Zone 2 intensity. Despite the seemingly clean chemistry, your body’s energy systems are messy, complex, and see a lot of overlap.

There isn’t a clear on/off switch for your energy systems. It is only when you transition between zones and change your level of exertion that one energy system temporarily dominates over the other. There is always more than one energy system functioning in your body. Distributing your exercise between these zones will help you train each system’s efficiency. But it all starts with a strong aerobic base. Spending between 70–80 percent of your workout in Zone 2 and the rest between Zones 4 and 5 can help you see the benefits of burning more fat and saving the limited carb-based fuel for higher intensities.

Here’s one method you can use to monitor your aerobic progress over time. Observe your heart rate and pace/watts over a long workout of around 60 minutes or more. Be sure to perform at a constant Zone 2 pace. After the workout, check how your heart rate trended during the exercise. If it was steady throughout, then you’re considered to have had minimal ‘cardiovascular drift’, which would imply that you have built a good aerobic base. You can now see yourself going longer and farther at the same heart rate, without losing your breath or need as many breaks as you did before.

Conclusion

Heart rate zone training uses your heart rate to define the boundaries of your workout. It is common to train on a scale of 5 zones, where each zone is a percentage interval of your maximum heart rate. Training your body in Zone 2 helps improve its ability to utilize fat as a fuel source, while also improving the efficiency of other energy systems. Zone 2 training helps build mitochondrial density (the number of mitochondria in your muscle tissue), increases ATP production, and improves lactic-acid clearance. Increasing the time spent in Zone 2 can help you build a strong aerobic base that can significantly improve your performance and longevity.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are for general information and educational purposes only. It neither provides any medical advice nor intends to substitute professional medical opinion on the treatment, diagnosis, prevention or alleviation of any disease, disorder or disability. Always consult with your doctor or qualified healthcare professional about your health condition and/or concerns and before undertaking a new healthcare regimen including making any dietary or lifestyle changes.

References