Your body isn’t equally equipped to handle stress at every hour of the day. The worst time to experience stress is at night, when your circadian system is tuned for rest and recovery.

While daytime stress can sharpen your focus and enhance performance, the same physiological response at night disrupts sleep quality and undermines next-day resilience.

In the evening, the body gradually begins its wind-down process. The level of melatonin, the “slow down” hormone, rises.

The brain starts preparing for rest, setting the stage for a smooth sleep onset and deep, restorative sleep, which is crucial for growth, memory, immune function, physical repair, and memory consolidation.

Circadian phases explained

| Circadian phase | Approx. window (relative to schedule) | Physiological state | Effect of stress | Likely markers | Practical note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase advance | 4-6 hours after minima | Cortisol rising (CAR), core temp climbing, and melatonin is low | Stress is tolerable but cumulative; sustained load builds recovery debt | Stable or higher HRV, normal resting HR | Good for demanding cognitive or physical tasks. |

| Circadian dead zone | Mid biological day — ~6–10 hrs after wake | Alertness steady; light has little phase-shifting effect | Stress is tolerable. | Gradual HRV decline, mild HR elevation | Use breaks to prevent overload. |

| Phase delay | Evening — ~2–4 hrs before bedtime | Melatonin rising, core temp falling, body winding down | Stress poorly tolerated and can delay sleep onset and fragment early sleep | HRV down, resting HR up at bedtime | Stop stimulants/exercise; protect wind-down. |

| Circadian minima | Late night — ~1–2 hrs after sleep midpoint | Core temp & HR at lowest, cortisol suppressed, melatonin peak | Lowest stress tolerance; stress easily provokes awakenings, impairs next-day recovery | Sharp HRV dips, HR spikes, sudden arousals | Guard this window; maintain dark, calm, stable environment. |

Circadian minima explained

Late-night work demands, unresolved worries, or an ill-timed workout increase evening stress. In turn, it interrupts the evening transition, resulting in delayed sleep onset, disturbed sleep quality, and a reduction in restorative sleep.

The disruption becomes even more pronounced during the circadian minima, the lowest point of the circadian rhythm. It typically occurs during the second half of the night, a few hours before awakening, when the heart rate and core temperature are at their lowest and the stress hormone cortisol is suppressed.

Stress during this period can fragment restorative sleep and trigger sudden awakenings, leaving behind residual fatigue the following day. Since the cortisol level is low, the body’s normal stress response – which relies partly on cortisol – is muted.

Nighttime stress also leaves behind measurable traces in the body. Heart rate variability (HRV), a biomarker that tracks the body’s response to stress and recovery balance, often drops while the resting heart rate increases. The body is in a state of alertness when it should instead be repairing and recovering.

One rough night might not seem like a big deal: You push through, catch up on coffee, and move on. But when stress keeps stealing your nights again and again, the effects add up. Regularly disrupting your sleep doesn’t just leave you groggy; over time, it can lead to a higher risk of heart problems, weight gain, low mood, and trouble managing emotions. In other words, night-time stress isn’t just about losing rest in the moment – it can slowly chip away at your long-term health and resilience.

How to protect circadian minima from stress

The practical takeaway is clear: stress tolerance is significantly lower in the evening and at night. Protecting these hours requires deliberate action. Establishing wind-down rituals such as reading or journaling, practicing good light hygiene by dimming artificial lighting, and engaging in breathing exercises all help wind down and reduce chronic stress, leading to better sleep and restoration.

First, learn to spot signs of nighttime stress. Your body’s most vulnerable point is the circadian minima, which usually falls about one to two hours after your sleep midpoint. Looking back at the past week, watch for heart rate or stress spikes, or repeated awakenings during this window.

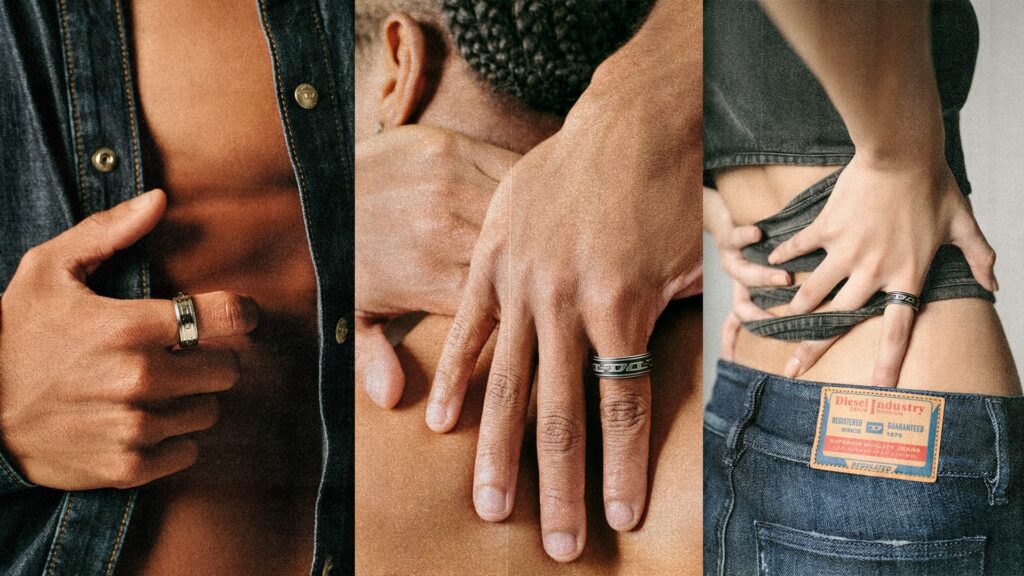

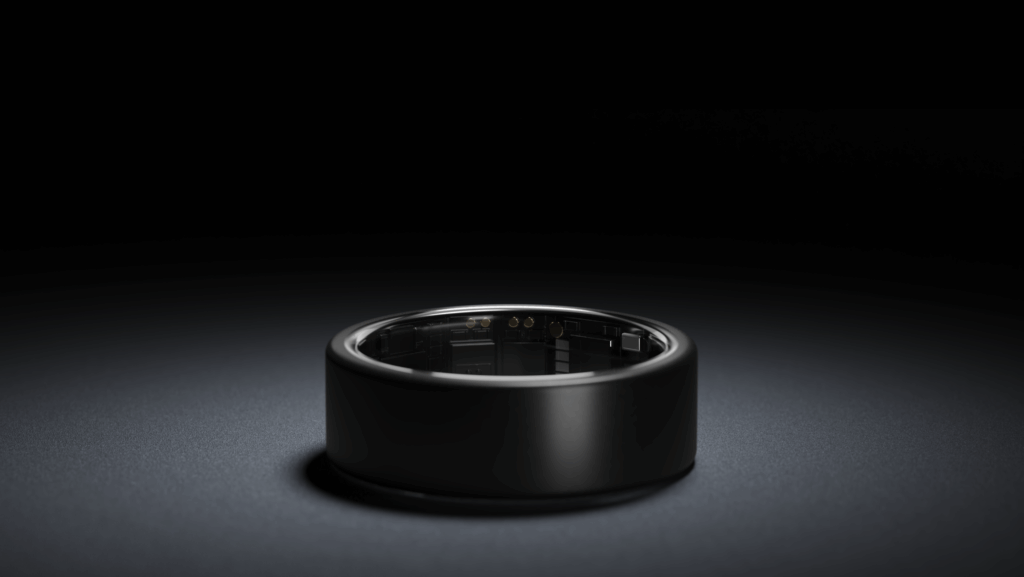

Here, tools like the Ultrahuman Stress Rhythm Score can help. This score highlights whether your body is relaxed, stimulated, or stressed in particular phases of your circadian rhythm. Avoiding stimulation or stress during your wind down, sleep, and minima stages – and taking steps such as breathing exercises or non-sleep deep rest (NSDR) to boost recovery can promote better sleep.

Other techniques could include:

- Put a hard stop on demanding work at least three hours before sleep. Keep high-intensity workouts six hours away from bedtime, saving evenings for lighter mobility work instead.

- Pay attention to light hygiene: switch off bright overheads, use warm low lighting, and avoid screens for 60–90 minutes before bed. If you’re caffeine-sensitive, cut off intake by local noon.

- Journaling or writing lists before bedtime to clear your head can keep stress from spilling into the night.

Summary

The circadian minima is when your body is at its most rest-oriented and least stress-tolerant. Disruptions here don’t just wake you up; they interfere with hormone rhythms, cardiovascular regulation, and recovery, leaving ripple effects across the following day. Use the Ultrahuman Ring AIR to easily monitor your stress rhythm and take steps to adapt to your lifestyle.

References

- Bailey SL, Heitkemper MM. Circadian rhythmicity of cortisol and body temperature: morningness-eveningness effects. Chronobiol Int. 2001 Mar;18(2):249-61. PMID: 11379665.

- Goldberg ZL, Thomas KGF, Lipinska G. Bedtime Stress Increases Sleep Latency and Impairs Next-Day Prospective Memory Performance. Front Neurosci. 2020 Jul 28;14:756. PMID: 32848547; PMCID: PMC7399217.

- Léger D, Debellemaniere E, Rabat A, Bayon V, Benchenane K, Chennaoui M. Slow-wave sleep: From the cell to the clinic. Sleep Med Rev. 2018 Oct;41:113-132. Epub 2018 Feb 5. PMID: 29490885.

- Akerstedt T, Kecklund G, Axelsson J. Impaired sleep after bedtime stress and worries. Biol Psychol. 2007 Oct;76(3):170-3. Epub 2007 Aug 6. PMID: 17884278.

- Goel N, Basner M, Rao H, Dinges DF. Circadian rhythms, sleep deprivation, and human performance. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2013;119:155-90. PMID: 23899598; PMCID: PMC3963479.

- Kim EJ, Dimsdale JE. The effect of psychosocial stress on sleep: a review of polysomnographic evidence. Behav Sleep Med. 2007;5(4):256-78. PMID: 17937582; PMCID: PMC4266573.

- Glosemeyer RW, Diekelmann S, Cassel W, Kesper K, Koehler U, Westermann S, Steffen A, Borgwardt S, Wilhelm I, Müller-Pinzler L, Paulus FM, Krach S, Stolz DS. Selective suppression of rapid eye movement sleep increases next-day negative affect and amygdala responses to social exclusion. Sci Rep. 2020 Oct 14;10(1):17325. PMID: 33057210; PMCID: PMC7557922.

- Morris CJ, Purvis TE, Hu K, Scheer FA. Circadian misalignment increases cardiovascular disease risk factors in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016 Mar 8;113(10):E1402-11. Epub 2016 Feb 8. PMID: 26858430; PMCID: PMC4790999.