The Wim Hof method is based on the belief that we, as humans, have grown overly comfortable in our modern surroundings, that we no longer battle the extreme temperatures and harsh environments and are losing our incredible power to adapt by giving way to homeostasis—a state of steady internal and physical conditioning. This method claims to be able to correct that—to voluntarily influence the autonomic nervous system as well as the body’s innate immune response to revive this allegedly immense, dormant capacity.

Highlights

- Wim Hof, is a Dutch extreme athlete who has a noted ability for withstanding freezing temperatures, running a marathon barefoot in the snow and climbing a mountain shirtless,

- The ‘method’ that allowed Hof to perform such feats invited scientific interest and led to a series of studies that sought to uncover his bold claims,

- Wim Hof is now described as a ‘global health leader’ and motivational speaker, with 21 Guinness World Records.

This is a bold claim, given that the autonomic nervous system is a control system in our body that acts largely unconsciously and regulates bodily functions, such as our heart rate, digestion and respiration. This system is further divided into the sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic nervous system—the former being the primary mechanism that controls our reflexive fight-or-flight response.

Who is Wim Hof?

Wim Hof is a Dutch extreme athlete who has a noted ability for withstanding freezing temperatures. He started his career with a circus act, trying to shock viewers with how long he could stay covered in ice —often significantly over an hour. This earned him the epithet ‘The Iceman’, and he went on to perform more seemingly impossible feats like running a marathon barefoot in the snow and climbing a mountain shirtless.

The ‘method’ that allowed Hof to perform such feats invited scientific interest and led to a series of studies that sought to uncover his bold claims, such as voluntarily affecting the autonomic nervous system, influencing the immune system, and adapting to extremely cold temperatures. With 21 Guinness World Records, Wim Hof is now described as a ‘global health leader’ and motivational speaker, with a significant following that practises his famous ‘Wim Hof’.

What is the Wim Hof Method?

Wim Hof describes his method as one that consists of three ‘pillars’.

Pillar 1: Breathing exercises

Wim Hof’s breathing technique involves cyclical periods of hyperventilation followed by breath holds, where you are invited to pay attention to your body. To hyperventilate is to ‘breathe rapidly’, but this isn’t the usual panicked style of hyperventilation—rather, it is a controlled, modified form of it. Each iteration of this exercise is called a ‘round’. You can do as many rounds as you like—as long as it feels good and you aren’t forcing it. Wim advises that it is best to do between 3–4 rounds, always on an empty stomach.

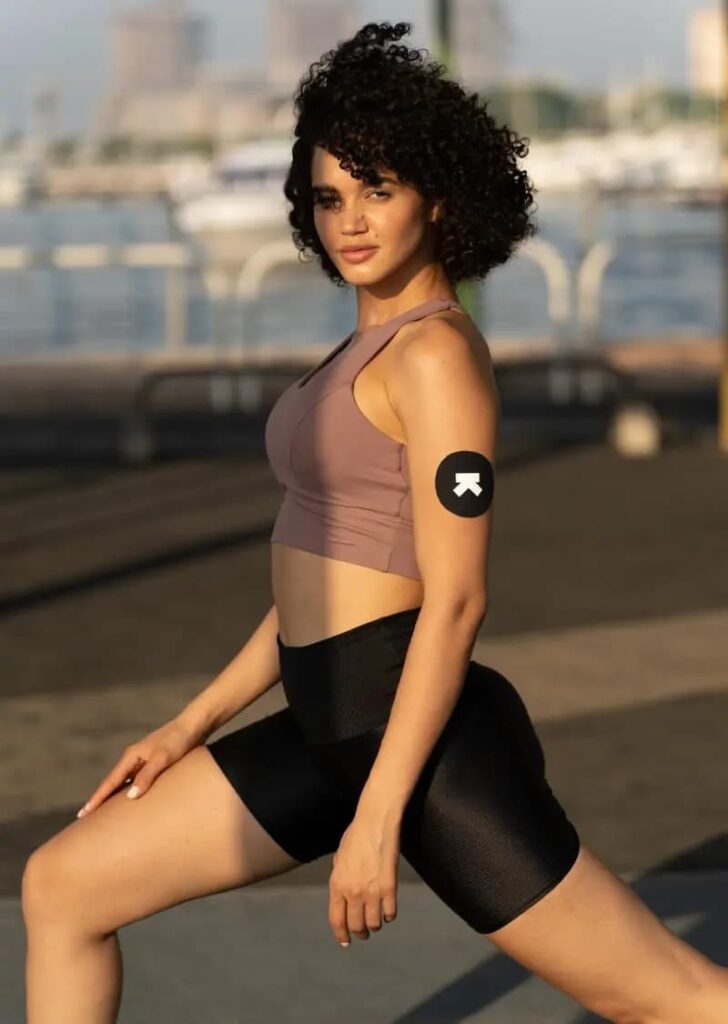

Pillar 2: Cold exposure for tolerance

This cold-exposure element of the method is strongly linked to the idea of letting your body interact with harsher environments. Wim Hof advises frequent, controlled exposure to the cold with the objective of building your body’s tolerance and stress response. In the absence of ice baths, Wim advises taking a cold shower for its effects on vascular health, mental strength and muscle fatigue.

Pillar 3: Meditation for focus

This final pillar closes in on the capacity of the brain and promotes the ‘mind over matter’ approach to mental strength and commitment. With stress response being a focal point of the Wim Hof Method, Wim advises you to calmly approach the various ‘stressors’ in your life. He emphasizes the importance of not ‘forcing’ yourself to fight the stress, but instead acknowledging, accepting and facing it steadily. Hof says that developing a focused mind is essential to the other two pillars and is therefore central to the Wim Hof Method.

Tummo Meditation, Thermogenesis and the ‘Brain Over Body’ study

In 2009, Wim Hof set the world record for the longest time in direct, full-body contact with ice, clocking in at 1 hour, 42 minutes and 22 seconds. The body naturally reacts to the cold in order to preserve heat and energy. It constricts blood flow to vital areas and makes us shiver to generate heat.

Cold is interpreted by our bodies as a noxious experience or a painful stimulus—a person becomes hypothermic when their core body temperature drops below 35°C, and when left untreated they are prone to heart/respiratory failure and, eventually, death. Our body generates heat in a process known as thermogenesis. One way of generating heat while experiencing cold is through ‘shivering thermogenesis’, where the body works its muscles by shivering to generate heat.

Another way is through ‘non-shivering thermogenesis’, where heat is generated without shivering and through the burning of special fat reserves. Scientists sought to study how Wim could stay in full contact with ice for extended periods of time while being fully communicative and without any noticeable shivering.

Wim attributes his success to the three pillars of his method. Although practices involving deep breathing, cold exposure and meditation have always existed, Wim insists that it is their combination that sets his method apart from other techniques. Individually, however, these pillars of the Wim Hof Method aren’t fundamentally new creations. Similarities have already been noted between Wim’s breathing technique and g-Tummo or Tummo meditation. Tummo (often pronounced ‘dumo’) is a sacred Indo-Tibetan practice that uses deep breathing and visualization techniques designed to release one’s ‘inner fire’.

It is said that the monks who practised Tummo meditation could generate enough heat to dry wet sheets wrapped around their bodies. Some say that this released visible amounts of steam, all while the monks sat or walked in the freezing cold of the Himalayas. A study published in 2013 sought to examine the neurocognitive and somatic components, i.e. the mental and physical components, respectively, of tummo meditation by testing two groups. One of the groups comprised expert meditators, while the other group (which served as the control group) consisted of Western non-meditators. The study showed that the expert meditators were able to generate heat through the physical act of breathing.

It appears that they were using their intercostal muscles, i.e. the muscles between their ribs, by inhaling and exhaling to generate heat. However, a key finding was that their breathing techniques alone were not enough to raise their body temperature. It was learned that deep focus (as seen through the alpha brainwave activity during Tummo visualization) was a primary factor in sustaining the heat generated through non-shivering thermogenesis. Neither the expert meditators nor the Western non-meditators could maintain their core body temperature without engaging in deep, focused meditation.

This discovery reveals a close relationship between Tummo meditation and the Wim Hof Method. In a 2018 study by Wayne University, Michigan, it was discovered that Wim’s capacity to tolerate freezing temperatures was largely influenced by his mental ability to ‘ignore’ the sensation of cold. This ‘mind over matter’ element of the Wim Hof Method is partly why this study is popularly known as the ‘brain over body’ study.

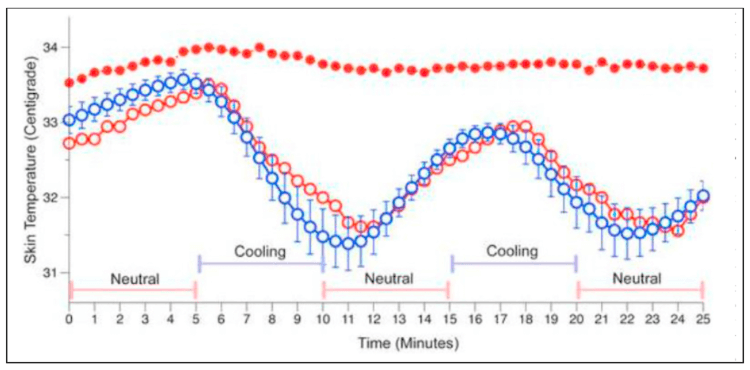

Wim was asked to wear a special, water-infused, full-body suit through which the scientists could pass temperature-controlled water. The suit allowed them to study how Wim’s brain and body reacted to the cold. Wim’s skin temperature behaved the same as anyone else when he did not perform the breathing method—it rose when there was contact with neutral water and dropped in the case of contact with cold water. But when Wim performed his breathing technique, he was able to maintain a steady skin temperature of around 34°C, regardless of the suit.

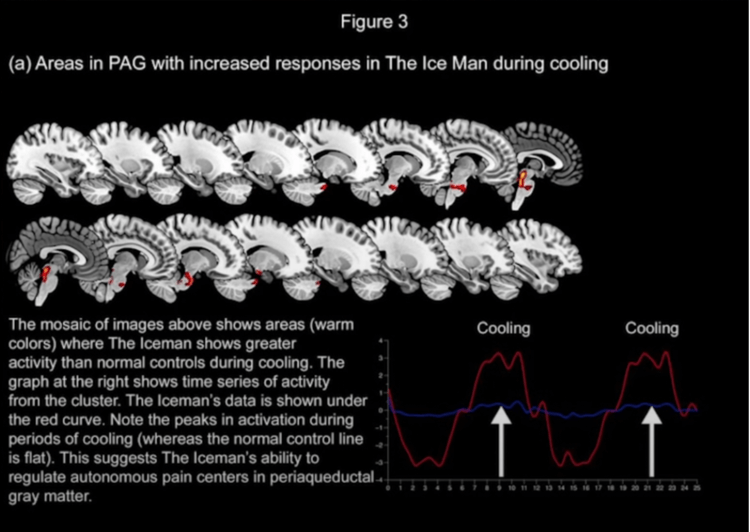

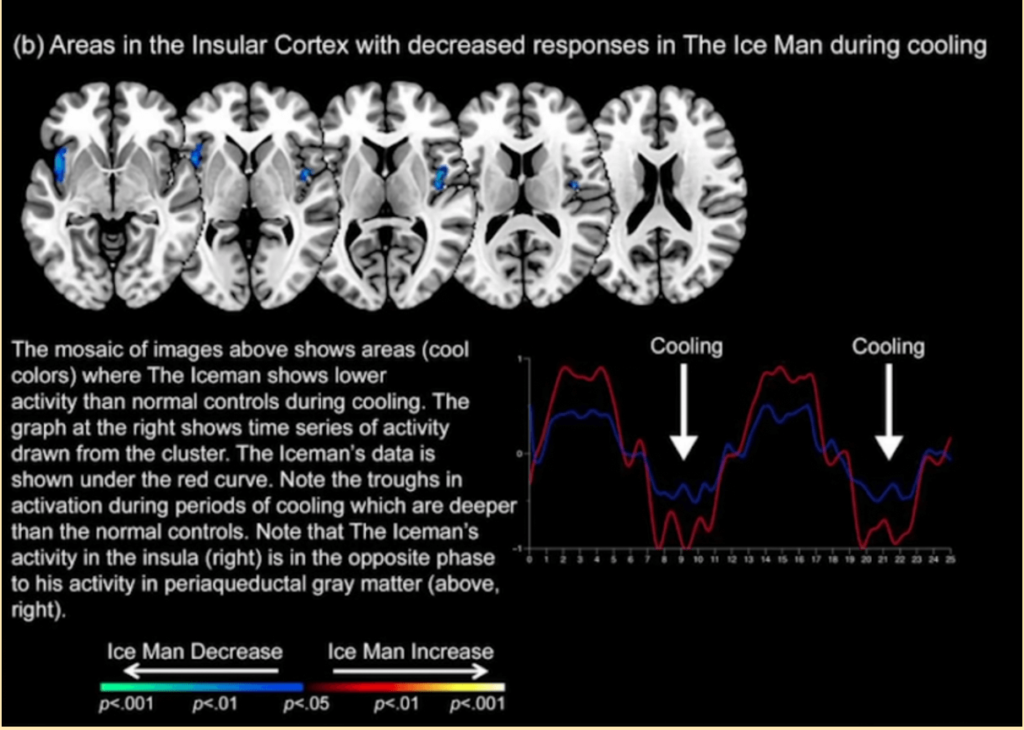

Here’s a graph from the study:

The empty blue circles represent the normal responses from the control group, the empty red circles represent Wim Hof when he’s not performing his breathing exercise, and the solid red circles represent Wim Hof when he is performing the breathing exercise. Excited by this finding, the scientists studied Wim through functional magnetic resonance imaging (or fMRI) scans (which measure and map the brain’s activity) and positron emission tomography (or PET)/computerized tomography (or CT) scans (which provide detailed internal images of the body) to see what was going on.

It was found that there was increased glucose consumption in Wim’s intercostal muscles, which generated heat and dissipated it to his lung tissue, thereby warming the circulating blood in his pulmonary capillaries (the blood vessels in the lungs). This stabilized his skin temperature at a steady 34°C without any significant deviations, despite the neutral – and cold-water stimuli. Further imaging revealed that Wim was able to activate the primary control centres in his brain’s periaqueductal gray (or PAG)—an area that plays a critical role in autonomic function and pain suppression—and used it to modulate the sensation of pain.

In addition to this, Hof’s engagement with the insula of his brain (a higher-order cortical area that is associated with self-reflection and internal focus) dipped and peaked much higher than anyone else in the control group. These results provided compelling evidence for the primacy of the brain over the body in mediating Wim’s responses to the cold. With such remarkable similarities, Wim is often asked about the difference between his method and g-Tummo breathing. He says that his method doesn’t require years to learn, is easier to access, and is more suited to the Western, sedentary lifestyle. Also, breathing can influence on blood glucose level of your body

Brown Fat, Twin Brother, and Mice

In 2007, Wim set a world record for the fastest half-marathon run barefoot on ice and snow, clocking in with a time of 2 hours, 16 minutes, and 34 seconds. In addition to Wim’s deliberate influence over his brain, it was also believed that he could consciously activate his body’s brown-fat reserves to generate heat.

Fat, also known as adipose tissue, is large in two types—white and brown. Most of our body fat is white adipose tissue (or WAT), which is used to store energy. Brown adipose tissue (or BAT) is significantly rarer than white fat and is used for producing heat through non-shivering thermogenesis. Newborn babies have a lot of brown fat, but this volume gradually decreases as they age into adulthood. To test whether Wim could affect his BAT levels, a study was conducted along with Wim Hof’s genetic twin brother, Andre Hof.

Andre lived a sedentary life, did not practise the Wim Hof Method, and didn’t have as much exposure to the cold. Both Wim and Andre were examined through PET/CT and fMRI scans to see if the Wim Hof Method could really influence brown-fat levels. Unfortunately, the results were inconclusive; there was no evidence that practising the Wim Hof method could either increase or activate brown fat in any remarkable manner.

It was, however, discovered that the Hof twins had much higher levels of BAT than normal, and were thus genetic outliers in this regard. In fact, Andre had a higher amount of brown fat than Wim did. It’s also worth noting that mice have been found to increase their BAT levels in response to repeated cold exposure. More research is required to prove this effect in humans.

Eustress and Distress

The stress response is a core element of the Wim Hof method. Wim speaks frequently about how unnecessary stress is and how it has been manufactured by humans. He advocates practising focus through breathing exercises and cold showers. In the case of cold showers, Wim advises approaching the stressor (the cold), without the mindset of fighting to survive it. Rather, he says to calmly accept the cold and allow yourself to get accustomed to it ‘without force’.

Studies have shown that his breathing exercises can help activate the sympathetic nervous system. This can trigger the fight-or-flight response, which aids the release of cortisol (the stress hormone) during moments of controlled hyperventilation. Wim believes that such positive stressors, also known as eustress, can help you adjust your reaction to sources of distress that are common in modern life.

Hyperventilation, Hypocapnia and Hypoxia

Wim’s breathing exercises start with a round of controlled hyperventilation—you are required to fully inhale through your nose and then ‘let go’ of the air through your mouth. There are no pauses while doing this; every inhalation is supposed to deeply fill your lungs and each exhalation is supposed to be ‘without force’. This is repeated between 30–40 times—a process that Wim describes as ‘charging’ the body. The volume of air you inhale and exhale is important, and in many of Wim’s guided breathing sessions, you can hear him say, ‘Not fully out, but fully in’.

After you exhale or ‘let go’ of your 30th or 40th breath, you are required to begin the ‘retention phase’. This is where you hold your breath and continue to maintain focus. Wim emphasizes that ‘retention’ is not a breath-holding competition, and that you can take your next breath when you feel your body needs it. When you feel the urge to breathe again, you are permitted to inhale deeply but are required to once again hold your breath—and this time for 10–15 seconds. This breath is termed the ‘recovery breath’. Once you exhale this breath, you will have completed one ‘round’ of the Wim Hof breathing exercise.

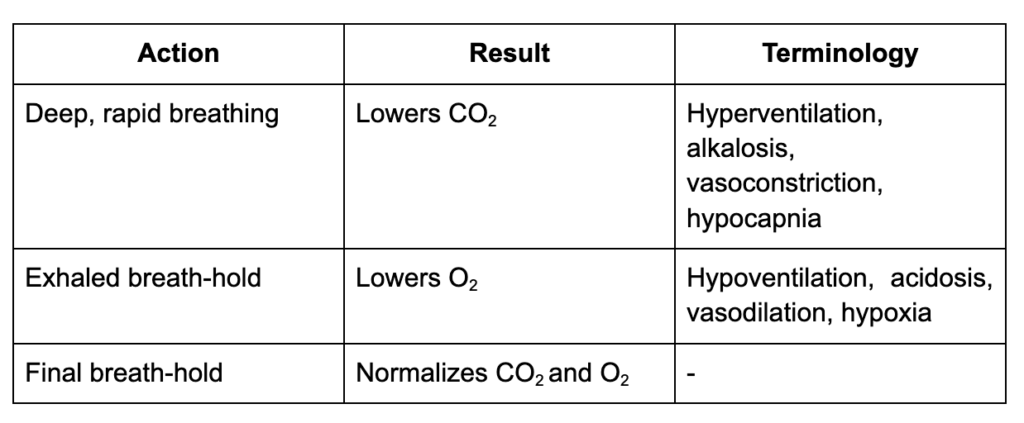

To summarize, each round is 30–40 deep breaths, followed by an exhaled breath-hold, and is completed with a shorter, inhaled breath-hold. Wim advises doing 3–4 such rounds without an interval. It may be tough to infer the physiological effects of this exercise or to link it to Wim Hof’s many achievements without looking at the science behind it.

It starts right from when you start taking the 30–40 breaths—several interesting things happen when you hyperventilate. Hyperventilation is more about removing CO2 than it is about increasing O2. When you breathe rapidly, you actively drop the amount of CO2 in your body. Your O2 levels don’t change much.

CO2 is a mild acid, and expelling it causes the pH of your blood to rise (you may remember that ‘acids’ have a low pH value, and that ‘bases’ rank higher). The pH value of an average healthy person is between 7.35–7.45, but hyperventilation can push it to around 7.50–7.75. A higher pH means your blood is more alkaline. And the lower level of CO2 that helps achieve this alkalinity is known as hypocapnia. Hypocapnia plays a major role in your ability to hold your breath.

Your desire to breathe isn’t triggered when your O2 drops, but rather by how high your CO2 levels are. You may also notice that your heart beats harder during the breath-hold. This is because hypocapnia causes vasoconstriction (the narrowing of your blood vessels), and your heart has to beat harder to get the blood through this constriction.

While you’re holding your breath, your body continues to use the oxygen in your blood and release CO2 into your bloodstream. Your oxygen drops and your blood is no longer alkaline. This drop-in O2 is called hypoxia, and this hypoxic state of stress triggers your sympathetic nervous system.

Your sympathetic nervous system stimulates the fight-or-flight response, which results in controlled stress response and is believed to be accompanied by the release of the stress hormones cortisol and adrenaline and endocannabinoids (which are neurotransmitters often associated with a pleasurable sensation of ‘euphoria’ following physiological stress, for instance, the ‘runner’s high’).

During hypoxia, your body attempts to restore the oxygen supply and therefore undergoes vasodilation, i.e. the widening of your blood vessels. When the levels of CO2 have risen high enough, the pons (nerve fibres that connect the medulla with the cerebellum) and the medulla oblongata of your brainstem trigger you to take a breath. This time, when you inhale and hold your ‘recovery breath’ for a shorter duration of 10–15 seconds, your blood gets a chance to normalize its levels of O2 and CO2. You then exhale to complete this cycle.

We have been using a lot of scientific terms. Here’s a table to help you follow the Wim Hof Method:

Blood alkalosis, as achieved through hyperventilation, can also have a significant effect on your ability to bear the pain. Have you ever noticed yourself breathing heavily when in pain—for instance, when you stub your toe? ‘Nociception’ is the name of the process through which your central nervous system detects pain. It is mediated by specific sensory neurons (or ‘pain-detecting’ nerves), a component of which is a protein called the acid-sensing ion channel 3 (ASIC3).

ASIC3 is a key area of focus for painkilling drug research. Interestingly, this protein is also quite sensitive to pH. A drop in pH can activate ASIC3, but an increase in pH to around the levels achieved through hyperventilation can deactivate them—thereby effectively improving the pain threshold. This explains how deep breathing and blood alkalosis can improve tolerance to a noxious stimulus like cold.

Poland, Endotoxin and the Wim Hof Immune Response

In 2007, Wim climbed to an altitude of 7200 metres on Mount Everest, wearing nothing but shorts and shoes. Despite the many accomplishments and world records that imply he is unique, Wim believes that his methods can be taught and practised by others. He believes that the body can be healed from within and that these methods can be used to influence the immune system and fight various diseases. In 2014, these claims were put to the test.

A team of scientists at Radboud University, the Netherlands, put together an experiment to test the Wim Hof Method’s ability to voluntarily influence the sympathetic nervous system and the body’s innate immune response. Male participants numbering 30 were randomized into two groups: a 12-member control group and an 18-member intervention group. The intervention group was personally trained for 4 days by Wim Hof himself. The training took place in Poland and consisted of various meditation, cold exposure, and breathing exercises. In particular, the group walked barefoot on the snow, swam in freezing waters, and climbed a mountain at an elevation of 1590 metres wearing only shoes and shorts.

The wind chill during the climb was between -12°C and -27°C. Upon their return from Poland, this group was required to continue the training at home for 5–9 days, where the cold-exposure requirement was taken care of through the use of cold showers. The control group, on the other hand, received no training. On the day of the experiment, all participants were injected with endotoxin (a piece of dead bacteria) to elicit their immune response. Typically, when injected with endotoxin, our immune system will flare up in order to fight it—even if the bacteria is dead. This can trigger various physiological changes like fever, headache, or nausea.

The scientists studied all participant responses by tracking metrics like blood composition, cytokines, white blood count, and so on. Also, cytokines, cell-messaging proteins that stimulate the functioning of the immune system, were a key focus during this study. It was found that the intervention group, trained in the Wim Hof Method, reported elevated levels of adrenaline and blood alkalosis in their body. Interleukin 10 (IL-10), an anti-inflammatory cytokine, rose sharply in correlation to increased adrenaline. Furthermore, the pro-inflammatory markers (namely, TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-8) were lower in this intervention group and correlated negatively with the levels of IL-10.

Even though the inflammatory response was suppressed in the intervention group, their white blood cells were not. Rather, the increased adrenaline caused leukocytosis, which is an increase in the white blood count. This showed that the immune system was still working in the background despite the dampened inflammation response. The intervention group committed to the breathing techniques for 2.5 hours of the 8-hour experiment. They reported fewer symptoms of nausea, headache, shivering and muscle/back pain, and their symptoms also reduced much faster than the control group.

In an earlier experiment, Wim Hof himself reported a slight headache that just lasted for around 10 minutes. These results showed that the Wim Hof Method could not only be taught and practised by others but also that it could voluntarily activate the sympathetic nervous system and suppress the innate immune response. This could have important implications for the treatment of conditions associated with excessive inflammation such as various autoimmune diseases. It is worth mentioning that the control group was quite disappointed at not being selected for the training imparted by Wim Hof, and were personally promised his guidance after the experiment.

Intriguingly, this suggests that the participants were already believers of the Wim Hof Method, which could have compounded a placebo effect. In 2015, the authors wrote a follow-up paper about how optimism and mental expectation of the outcome affected the result. Though this is the very essence of a placebo effect, it doesn’t necessarily trivialize the findings because placebos are a reflection of the body’s immense power to truly affect its own physiology.

What’s truly lacking, however, is research into the long-lasting effects of practising the Wim Hof Method. While it’s unlikely that the body’s homeostatic response will allow the pH value from blood alkalosis to last long, there is still scope for understanding how long the physiological effects, like increased adrenaline, endocannabinoids and anti-inflammatory markers, will last. This can help us better understand the scope of the Wim Hof Method with respect to autoimmune diseases.

Altitude sickness, Metabolic activity and the Cori cycle

One of the most compelling results of practising the Wim Hof breathing exercise can be its ability to circumvent altitude sickness. This illness occurs during ascent to high altitudes and is often accompanied by nausea and exhaustion due to the shortage of oxygen.

Some people are more prone to altitude sickness than others. The likelihood of the occurrence of this condition can be determined by a person’s hypoxic ventilatory response (HVR), which refers to the increase in a person’s rate of breathing as a result of hypoxia (low O2 levels). This rate usually returns to normal once they acclimatize to the altitude.

Some people are unable to mount an increased ventilatory response and are thus prone to altitude sickness. They are typically prescribed the drug Diamox, which causes mild metabolic acidosis (a disorder marked by a disturbance in the acid-base balance of the body) and subconsciously forces them to breathe faster and blow out CO2 in order to correct the pH levels. As a result of doing so, they breathe in more oxygen and avoid falling sick.

Consciously practising the Wim Hof Method during climbs can serve as an alternative to taking Diamox and avoiding altitude sickness. In the Journal of Wilderness & Environmental Medicine, it was advised that though one shouldn’t make their way up mountains too quickly, practising the Wim Hof Method can be helpful during urgent times—for example, in the case of mountain-rescue teams.

Presently, more research is being conducted into the Wim Hof Method. In 2020, Radboud University followed up on the endotoxin experiment with an article that looked further into the effects of the Wim Hof Method. It was learned that the breathing exercises resulted in increased activation of the Cori cycle and higher concentrations of lactate and pyruvate, which correlated with high levels of the anti-inflammatory protein IL-10.

The Cori cycle is a metabolic process that uses lactate and glucose to produce energy. Further research can help uncover more about the role these metabolites play in the anti-inflammatory results of training in the Wim Hof Method.

Exercising caution

One must take note of the warnings associated with the Wim Hof Method because the breathing exercise can affect motor control or lead to loss of consciousness. People suffering from heart disease, epilepsy, and migraines are generally discouraged from performing these exercises.

The Wim Hof Method is advised to be practised in a safe area while sitting or laying down, and never while piloting a vehicle or while in or near bodies of water. Prof. Dr Wouter van Marken Lichtenbelt, one of the researchers who studied Wim, is known to have said that it wouldn’t hurt to try the Wim Hof Method—with some ‘common sense’ and without ‘excessive expectations’.

Conclusion

The Wim Hof Method consists of three pillars: breathing exercises, focused meditation and cold exposure. Many scientific studies have been conducted to review the effects of performing this method. While there are compelling results showing that practitioners can influence their sympathetic nervous system as well as dampen their immune response, more research is required to ascertain the longevity of these physiological changes.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are for general information and educational purposes only. It neither provides any medical advice nor intends to substitute professional medical opinion on the treatment, diagnosis, prevention or alleviation of any disease, disorder or disability. Always consult with your doctor or qualified healthcare professional about your health condition and/or concerns and before undertaking a new healthcare regimen including making any dietary or lifestyle changes.

References

- Wim Hof Method

- Neurocognitive and Somatic Components of Temperature Increases during g-Tummo Meditation: Legend and Reality

- Voluntary activation of the sympathetic nervous system and attenuation of the innate immune response in humans

- Respiratory Alkalosis – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf

- Voluntary activation of the sympathetic nervous system and attenuation of the innate immune response in humans | PNAS