Introduction Of Podcast

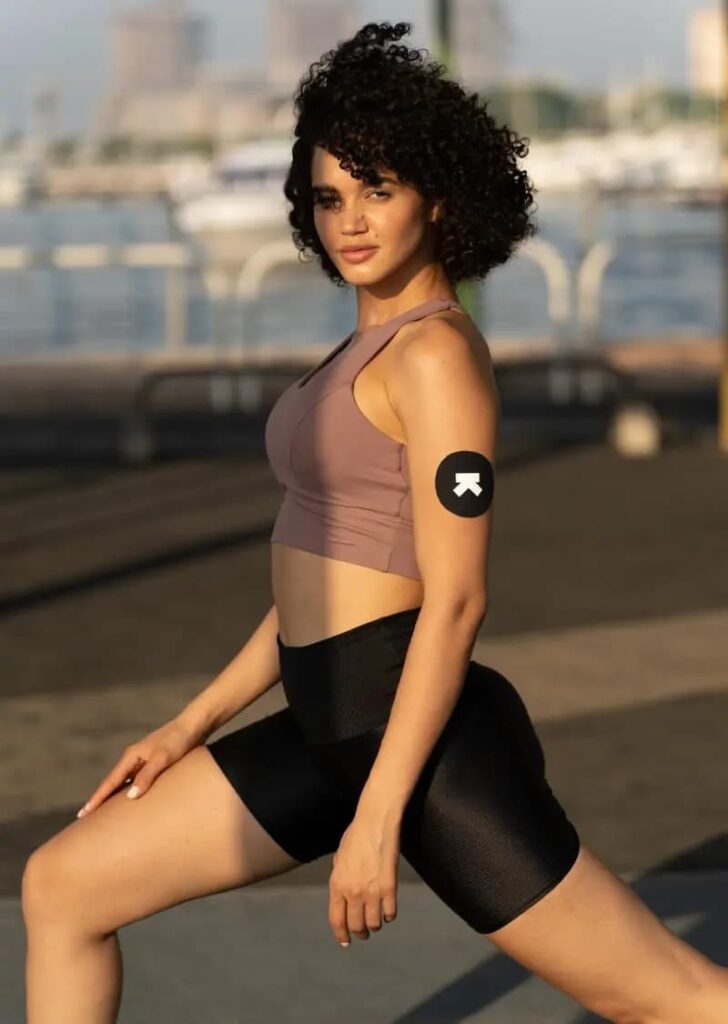

In this episode, Mohit & Shiva discuss everything about CGMs. How they came into existence and answer pertinent questions such as are CGMs meant just for diabetics? They also deep dive into how you can improve performance by optimising not only your diet, but your lifestyle based on personalised glucose biomarkers.

Timestamps

- (00:00- 01:35) – Introduction

- (01:39 – 06:49) – Importance Of Metabolic Health

- (06:50 – 10:18) – Precursors of Metabolic Disorders

- (10:19 – 13:21) – Diabetes: Reversal vs Avoiding

- (13:23 – 17:33) – Relation of Glucose to Oxidative Stress

Key Takeaways – Transcripts

Intro (Mohit): So, this is a fun fact. The first professional CGM was approved by the FDA in the year 1999. And if you really think about it, CGM is the way to measure. But continuous glucose has really changed the game around how people look at metabolic disorders, specifically diabetes, right? Because the way you would diagnose diabetes or even manage it used to be on the basis of static measurement mechanism, most probably a fingerprick. Besides from being extremely painful, the method that actually gives you continuous points is way more comprehensive set of information pointers around what your lifestyle is because then you can measure your glucose variance, variation during sleep, you can measure it post peronedial, you can measure it in response to exercise. And that tells you a lot about your own body. So CGMs really changed the game way back in 1999. And CGMs obviously have been evolving as different companies in the space have been realizing that lifestyle plays a mega role in terms of helping people understand their metabolic disorders, but also to avoid these. If you have been curious about why measurement of glucose in a continuous way matters, I think you’re in the right place. Let’s get to it.

Question (Mohit): A common question that we get asked is why should I really pay attention to my metabolic health? I don’t really have a problem. I think that’s an interesting question because probably there are two types of people. One is people who want to on the left side of the Bell curve, they want to be peak performers. And then on the right side, you obviously have people who face a problem, then they react, and then there’s a spectrum, right? I mean of people sometimes reacting, not reacting, essentially, right? But what is the ideal, let’s say, perspective around this? When should people really think about and how should we think about their metabolic health, starting from, let’s say, the left side of the spectrum, left side of the spectrum, which is performers, how should they think about metabolic health? The middle and the far-right side, essentially?

Answer (Shiva): I think that to be able to change on that, the first question is the objectives of these three different sections of people has to be considered, right? A performance guy may want to increase his performance, right? Or increase his ability to consume a variety of foods. These are the two things because often they get like into a very contained diet and over a period of time that could have an issue on your metabolism. What we noticed is that they lose a lot of diversity in the gut, and they begin to have gut problems later on and a high amount of cortisol problems because the fueling strategies may not be optimal. They’re fueling for only performance. They’re not fueling for health. You got to understand health span and lifespan are two different elements, right? Lifespan is almost the antithesis of overdoing it, and performance is all about overdoing it. If you think about what the modern day like Peter Sinclair is talking about is all about calorific restriction. You’re talking about minimal movement. It’s actually very very interesting. It’s the exact opposite of what you’d be doing if you’re a performance athlete, isn’t it? I mean, you have to consume so many calories. You have to be doing this much. You’re going to be utilizing the stem cells. Your heart rate is really high level, right? It’s really interesting.

(Mohit): I like that you said Peter Sinclair because it’s Peter Attia and David Sinclair in one.

(Shiva): Yeah. Oh, yeah. Sorry. That’s right. Exactly. Yeah.

(Mohit): It’s a great shortcut to talk about longevity, right?

(Shiva): So, if you think about that, that’s the performance aspect. And now the middle guys who are talking about they’re actually quite an optimal place.

(Mohit): Before we get there, I think you bring up a really interesting point around athletes, right? That the athletes that you see around for maximizing everything might not be the healthiest people around. Then for athletes, this is actually their longevity, even if you look at it from a performance perspective, like, how long can I keep doing this? Do I want to be a five-year athlete, ten year athlete or 15 year athlete? So, their longevity in sports career and overall longevity, that gets determined sometimes by looking at like, yes, “I’m optimizing for performance, but am I actually performing within the realm of longevity as well or not?” So basically simplifying, call it longevity for performance, for example.

(Shiva): Right, absolutely. And then now you’re looking at the guys who are like having an issue with metabolic health. They are considering it, but are they looking at lifestyle? Look, we know that exercise and a lot of the tools have been there forever. Nobody wants to utilize them. I don’t think it’s a problem of the tools or the solutions. I think it’s a problem of motivation.

Question (Mohit): So, there’s this left side of the spectrum, which is peak performance athletes. For them, it’s longevity. What’s in it for, let’s say the middle spectrum, people who might have one or two of these symptoms or one or two of these problems, but they are not critical enough?

Answer (Shiva): Actually, I think metabolic syndrome is three of those problems. And your metabolic syndrome. So, if you have high triglyceride level, if you have high blood pressure, hypertension, if your uric acid levels are high, and obviously if you don’t have control over your blood sugar, they’re already heading very close to metabolic syndrome already.

Question (Mohit): Even if you don’t have diabetes?

Answer (Shiva): Yeah. Those are the precursors, right? So even if you have a high triglyceride level and then you’re sort of getting prediabetic, you’re already heading towards there. And according to a lot of the recent research, if you look at it like I think they’re saying 90% of at least the US have some of these happening, even if one or two, three is not too much of a problem because that’s the next logical step. So, if you have hypertension, you better start still managing the glucose because they sort of are a series, right? I mean, there are things that are interrelated. So, if you really want to sort that out, it’s not one and two is still like a great time to manage it because you won’t go to the other side of the spectrum.

Question (Mohit): So, you’re saying that these are all early markers. Yes, of metabolic disorder, and basically almost 90% of the population has one of these markers. So that just simplified for me. For example, you mentioned triglyceride. What would be the long list of things to watch out for when you’re looking at, do I have a metabolic disorder or not?

Answer (Shiva): I think your HDL will be lower. Your triglyceride levels will begin to go up, right? Your fasting glucose, you’ll see it up occasionally. It will be your insulin; your insulin levels will be up. Visceral fat is another great one to look for, right? They basically figured out that a lot of diabetic people have it’s called the athletes paradox. This is amazing. So, a lot of people with diabetes have a lot of intramyocellular fat. It’s fat inside your muscles and they can’t access it. Right. I mean, that’s part of the problem because they can’t access it, and fat keeps getting dumped over there. But so does an athlete. They have the same amount of fat in the muscle. The regular guy who’s, like in between, does not have that, right? But the athlete has. Why? Because he’s using that in a high amount of flux. His mitochondria is just burning through it. So, the problem is actually in the way the mitochondria functions, ultimately. So, you’re talking about mitochondrial health, right? Which is the next frontier, so to speak. So, if you’re able to get the mitochondria to burn and do the fatty oxidation, you will get through this.

(Mohit): That’s why the brown fat and everything else.

(Shiva): Exactly. So, then you see how light again makes a big difference and how you want to balance all the micronutrients and the nutrient sensing and make sure there’s less oxidative stress. And all of these things are tied in, right? So, when you’re in the middle, that’s why you have complete control of moving it into the left side direction or making sure you don’t further and go into a diabetic issue, because a lot of people are shocked when they get there. But even stress will get you there. Lack of sleep will get you there, right? As we discussed earlier. So, it’s not just a one-shot thing. And that’s why it’s intriguing, because if you look at it from that kind of holistic perspective, right? It gives you that everybody, by observing, will be quickly able to change, In the Cyborg, I know you already have a lot of data on how people quickly changed just watching themselves. Actually, it’s the best tool that’s a guide to help you change, right? I mean, and we’ve seen this over and again. Even with myself, you see the things that you react to, and you take a conscientious decision knowing that you’re going to be reacting to it. And what the Cyborg does is gives you accountability, right? And that’s all you need. You just need somebody to keep you accountable. You can’t make them accountable. You have to only be accountable to yourself. And this gives you a choice of whether you want to be accountable at that point in time or not. And then you can remedy that, right? You have an action so you can say, listen, today I’m going to have, I don’t know, eat Haagen Dazs ice cream or whatever it is, and then I’m just going to go for a light walk after that, right I remember you were talking about walking in the morning as well. I mean, you just do it because it does. Whether you know it or not. There are these subtle things. The good news of our education system is made us not want to fail, especially when you see numbers you’re like, man, I don’t want to be on the other side of that, right? And that’s really interesting because now that’s something that we’ve programmed early, and it’s sort of working for us. When you see these graphs and data and saying you’re not on this end of the bell curve, on the other end, you’re like, oh, no, maybe I should do something about it. So, it becomes interesting. And I think that middle portion is a huge one, right? Yes. Longevity for performance. But the middle one is the real preventative part, right? That’s where you’re at.

Question (Mohit): When should you act? There is a preventive versus curative view to that. Of course, prevention is better than cure in many ways. I mean, it’s a common quote, but is there a biological reason to prevention being better than cure as well? But I’m essentially asking is that reversal of a metabolic disorder, like, for example, in this case, let’s say let’s look at diabetes, reversal of diabetes versus avoiding diabetes. If I just look at pure ROI, huge. So how hard are these two problems? If you compare and weigh these two?

Answer (Shiva): The amount of energy you need to use to reverse diabetes is going to be an enormous undertaking because you’re already on this side and depends on how far this side you are. And you may or may not be able to do it economically. Right. You have insulin, maybe you have other things that you need to take. You have pharmacology, you’ll need to be able to manage it. You may need to do like a whole bunch of things like you have to do the prick test. Suddenly it becomes all these added things that you need to do not only to spend on, but also to take time off to do. Sure.

Question (Mohit): No, I think there is this part, which is obviously the part that there are a bunch of things that you need to do which are over and above preventing a metabolic disorder to reverse diabetes, right? But are there also biological changes that happen in the body, permanent biological changes, semipermanent or permanent biological changes that have long term effects? For example, what I’m trying to say is that somebody who has reversed diabetes and gotten back to an Aboriginal state or versus somebody who doesn’t have diabetes, their HB events are similar, right? Their glucose levels are similar and comparable. Are these two bodies different?

Answer (Shiva): I’m sure there will be because your insulin sensitivity will not be the same, right? Once you have this kind of resistance, your body will be prone to it and much more tuned towards resistance, insulin resistance than otherwise. And insulin resistance is the reason that you are diabetic. So, with insulin resistance comes so many other problems in terms of performance because you are able to store only half the glycogen you can traditionally store, which means your performance is going to be half, right? So, it is going to be a much harder living. Those changes are going to happen even on a cellular level, right? It’s going to happen over there. And plus, the oxidative stress, all those other things, your efficiency of your metabolism, all of that is going to be a little more compromised, and your sensitivity to certain foods are going to be way higher. So, your choice is going to come down, right? The ability to live is going to be more difficult. And that’s the amazing thing about what you’re talking about, that in between person has a choice to not go down that route. Yeah.

Question (Mohit): So, I think just highlighting one aspect of what you just mentioned, you mentioned oxidative stress, right? And for our listeners, when we think about glucose, we almost always think about the sequence of mismanagement of glucose leading to diabetes. But then there are so many disorders associated broadly classified as metabolic disorders. But then oxidative stress that basically just spoke about would have, let’s say, wider consequences. Is there a correlation with glucose to oxidative stress as well, and why is it important to watch glucose from an oxidative stress perspective?

Answer (Shiva): I think it’s got to do specifically with glucose variability. When you are spiking it up and down, think about the variability of the glucose itself and how the mitochondria has to deal with it. I know that it causes a lot of reactive oxygen species, et cetera, because when you have a high amount of glucose, there are multiple things that are going to happen, right? A high amount of glucose, it depends on the quantity, of course, can actually be converted into fructose because in your portal vein you have a conversion mechanism to fructose. And fructose is also because it’s actually quite corrosive in multiple ways will cause other problems. Now that could be like in the kidneys, right? Especially. So, then you’re going towards the blood pressure, and that kind of stuff. On the other hand, on the mitochondria itself, every time you are processing any kind of food, you are going to have like an oxidation event because the processing itself has it. But the more you put off this unadulterated glucose or whatever it is going into your system, and especially when it’s on and off, you’re going to create a greater amount of variability because the greater amount of glucose you have and if it’s spiking and it’s coming down and spiking and coming down, one of the things you can be rest assured is that we create more fat, right? And out of this fat, you’re going to have a lot of these metabolically active fat. And some of those things that we discussed before, which is that diastyle glyceride, like the triglycerides, the ones that are going to stop this glute for receptor. So, it is going to inflame your cells, so to speak. And this fat is going to be all over your body, right? And deposited at various places. Yeah. Especially visceral fat around your organs. It’s also for atherosclerotic issues, right? For cardiovascular issues as well. So, if you think about it from that perspective, this small thing that is oxidative. Yes. Because why is it oxidative? The mitochondria is to basically use glucose through a process called oxidative phosphorylation. It needs oxygen and glucose. Now with a huge amount of it. It all gets stockpiled outside, and only some of it is coming in. The other one is going through on the lactate pathway. And then you have some of it being converted into fat, right? Those are all the variations that you actually have happening. So, you’re creating a greater amount of oxidative stress. Now, this oxidative stress is interesting. What does that mean? This means that this oxygen molecule is highly reactive and begins to damage cell membranes, begins to do all of that inflaming the system more, right? Now, when it gets inflamed, what happens? You have cytokines. Now, everybody knows about cytokines after COVID. So, you have IL six and tumor necrosis factor that is like all over your body. And these are cytokines that are saying we have inflammation, then there are more white blood cells coming in and cleaning up that mess. But the problem with immunity is a very strange thing, right? When immunity is so triggered all the time, it’s easy to go into an autoimmune condition. It’s also easy for immunity to cause other issues, like the plaque formation around your cardiovascular area. But you see it’s all related, isn’t it?

(Mohit): Physiology, right? The interesting part is that just like nature, everything is related.

(Shiva): And that’s what I’m saying. So, it’s not just a problem, right? So, if you’re able to look at this small metric and say, listen, I know that I can do this sometimes, but I need to keep this under control, automatically you’re going to have to manage portion sizes. You don’t have to do it consciously. You’re going to do it without the quality of fuel and the quality of fuel because you’re going to be like okay doing it which means less impact on the body which means more efficiency, performance and inadvertently you’re going to be swinging back into more optimal States, right? Listen, it’s not like we’re not going to make bad choices. You’re going to make some bad choices, right? According to this model of behavior, the trans theoretical model of behavior, you’re going to fall off 67 times. It’s normal. That’s a human thing to do before you make a change. That’s like actually maintenance and sustainable. Everybody is going to fall off. Our problem is what we do when we fall off everybody. If you judge it too harshly, you’re never going to do the comeback, right and come back. Everybody comes back. Yeah, I mean look at Arnie, so you have to think about it from that perspective of saying that we have to allow people to do the comeback, right? And that’s how this is. This is the comeback. You can keep going and you’re like you’ll get better at every iteration as you have this control. It’s not a single shot thing. I’m going to stop Cold Turkey, so it doesn’t work like that.

(Mohit): The balance really makes a lot of difference versus basically taking an extremist approach in this case. But since you mentioned the role of glucose variability being linked to oxidative stress, It actually intrigues me when I think about it because then unless you measure glucose continuously, you will never have variability. So traditionally when we measured glucose point in time four or five times a day in case of diabetics or even in case of performance athletes, you could never understand variability. What that basically means is that as the science of continuous glucose monitoring or the coverage of continuous glucose monitoring rather emerges, we’ll probably have more evidence around the linkage between variability and different other health factors.

Outro (Mohit): Being able to measure glucose continuously is a game changer and I hope this episode has changed the way you’ll understand and view a CGM device. Let us know your experience of this by tagging us on our social handle @Ultrahumanhq on Twitter and Instagram. Thank you so much and we’ll see you soon.